HARMAN INTERNATIONAL

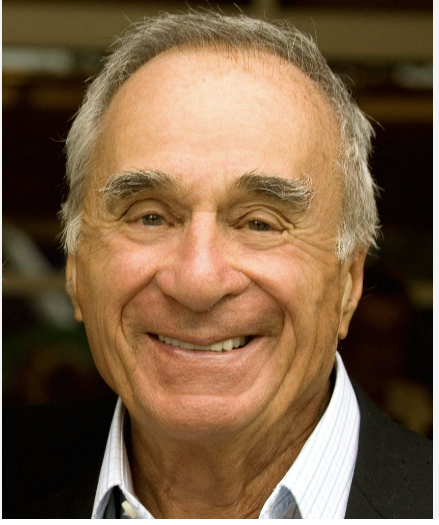

Sidney Harman cofounded a successful high fidelity audio products company in 1952. The company was named Harman/Kardon. For the rest of his life he remained involved with the company except for two brief departures described below. In both cases Harman sold the company and then bought it back a few years later. At the time of his death in 2012, Harman/Kardon was a unit of Harman International Industries; Sidney Harman was listed as the company’s Chairman Emeritus; and the company’s web site stated that, “ The story of Harman Kardon is largely the story of Sidney Harman.”

Throughout his years as a business owner, Sidney Harman found time to engage in community activities. He was active in the civil rights movement; he was active in various educational endeavors ranging from teaching, to administering to underwriting the cost of several targeted university programs at Harvard, City College of New York, and the University of Southern California. Near the end of his life he bought the once proud Newseek magazine and was actively involved in trying to turn it around at the time of his death.

In 2003 he published his autobiography, Mind Your Own Business, which had a subtitle descriptive of Harman’s approach to management ---- A Maverick’s Guide to Business, Leadership and Life. That autobiography is the primary source of this essay.

YOUTH

Sidney Harman was born in Montreal, Canada on August 4, 1918. His father worked for a hearing aid company there. The father later moved the family to New York City where he worked in a similar job. There Sidney grew up ( Arnold, 2011).

While still young, Sidney gained business experience as a newspaper delivery boy and as the head of a group of newspaper delivery boys. As he recalled that experience in his memoir many years later ( Harman,2003, pp.18--19):

“ I won a number of bicycles as rewards for the performance of my team, and I learned the value of sharing them with my associates. I also noticed that when we dropped off the day’s newspapers, there was often a collection of old newspapers and magazines left to be carted away by the building superintendent. With my first real entrepreneurial instinct, I instructed my boys to leave the newspapers but to carry off the old magazines. Then I commissioned a local tinsmith to fabricate some simple metal racks. I took the racks and the now--organized old magazines to (local) candy store proprietors and struck a deal with them. The racks were mounted inside the entrance to the stores; the magazines were sold, ‘pre--owned but reasonably current’ for five cents each, and I split the proceeds with the candy store 2 owners. That nice little business helped finance my years in high school and paid for my books in college.”

Harman received a tuition--free admission to the City College of New York ( CCNY) and graduated from there with a major in physics. His later reflections on his college days provide the following insight into his later approach to business ( Harman, p.174):

“(T)he informal, underground, virtual college at New York University overwhelmed the formal stuff at CCNY. It opened my eyes. It let me in on secrets. It challenged all the old assumptions, and, far more than I realized, it formed the basis for how I thought – and how I still think about everything: business, family, politics. Certainly my distaste for the orthodox, for the view that ‘this is the way it’s done,’ was incubated there.”

EMPLOYMENT WITH THE DAVID BOGAN COMPANY

Harman’s college experiences included concentrated study of science at City College and business at Baruch College, both colleges located in New York City ( two decades later, in 1973, he would earn a doctorate in social psychology from the Union Graduate School in Cincinnati).

Upon graduation he was hired as an engineer by the David Bogen Company, a New York electronics firm. The firm’s founder, Mr. Bogen, was a Russian immigrant who, “ had grown wealthy by buying surplus wire and cable from one General Electric plant and selling it, at a considerable markup, to another GE plant nearby. In those days one GE facility had no knowledge of what another was up to…” (Harman, 2003, p.20).

Harman’s initial assignment was to work in the engineering department at a small factory which produced public address equipment. The chief engineer there was Bernard Kardon with whom Harman would eventually start a new business. Kardon soon recommended that Harman be put on a management track. So Harman was made an office assistant to the factory’s sales manager, Haskel Blair. Initially Harman handled Blair’s correspondence.

Blair was an independent sales representative working on a commission basis. He worked part-- time at the job and was often absent. Harman was ambitious and saw in Blair’s frequent absences an opportunity to expand his scope of work. As he explained in his autobiography ( Harman, 2003, p.20)”

“ I realized that if I took the initiative and simply did something no one else was taking care of, I would get away with it unless it caused serious damage. Gradually, Mr. Bogan came to detect some modest ability in me and assigned me some of the responsibilities that had been Mr. Blair’s.”

Eventually Bogan assigned Harman to make sales calls on the wholesale radio parts companies which were the company’s customers. That assignment became an important professional growth experience for Harman. As he later explained ( Harman, 2003, p.21):

“When I began to travel the country in the early 1940s, visiting dealers and selling our products to them, I learned I had some talent for it. I liked to travel; I liked to study the products (ours and those of our 3 competitors); and I liked to sell them …Over time, as I became more skilled at travelling and selling, I became increasingly aware of what the end buyer needed. That prompted me to press for new products when I returned, and often those products succeeded because they met those needs. To this day, over a half century later, I can say that no valuable, enduring product ever arose from contemplation in my offices – or in the engineering department.”

In addition to making sales calls Harman was in charge of organizing and staffing the company’s exhibit at the annual industry convention in Chicago. Bogen and Blair would also attend occasionally but Harman was the only employee there full time.

Harman’s dedication and successes led to his appointment as the company’s sales manager. He was initially paid $50 a week. That soon seemed insufficient to him, partly because he was thinking of marrying a woman he had dating. So he asked for a raise. Bogen’s response followed by Harman’s actions became one of the more interesting episodes in his business career. As he tells the story in his autobiography ( Harman, 2003,pp.22--23):

“ I summoned my courage, walked into Mr. Bogen’s office, explained my circumstances, and asked if he would consider a raise in my salary. He said that he would think about it.”

“As long as you are thinking about it, sir, would you mind thinking about ten dollars?”

“ ‘ I don’t have to think about it’, he said, infuriated by my impudence. ‘You’re fired.’

“ “Fired? I don’t want to be fired. I love my job. And I’m learning so much”.

“ I ain’t running no school”

“ I left his office and returned to mine immediately next door. I did more. I returned to work and stayed with it diligently. Mr. Bogen was obliged to walk through my office ten or fifteen times a day as he left his own to walk the factory floor, check the mail, or review what was happening elsewhere in the firm. Not once in the next three weeks did he acknowledge my presence. .. At the end of that three weeks, I opened my weekly pay envelope. Behold! I was now earning sixty dollars a week.”

In 1944 Harman went on leave to join the army. By then he was married to his first wife and expecting his first child. In the army he worked on a sonic deception project at a secret location in Watertown, New York. There he had several work and rank promotions culminating in his honorable discharge as a second lieutenant at the end of the war. Several of his experiences during that period of his life are both humorous and instructive as told by Harman in his autobiography. ( Harman, 2003).

Returning to the David Bogen Company, Harman soon persuaded Mr. Bogen to authorize the development and sale of an electronic amplifier which, in contrast to the competition, operated with one control. The product was developed by Bernard Kardon and was a success in the marketplace. Harman was promoted to general manager.

Harmon and Kardon then began to study and experiment with public address amplifiers. They made custom systems which played 78--rpm records. They became convinced that the David Bogen Company could develop a profitable market. Bogen “reluctantly yielded” to their proposal and the company produced two high--fidelity amplifiers.

HARMAN/KARDON

By 1953 conditions were ripe for Harmon to set off on his own. One of those conditions was Bogen’s conservatism. Harman was frustrated by Bogen’s “reluctance” to approve new products. With respect to aggressive expansion in the high fidelity area, Bogen’s “heart was never in it.” Another consideration was the fact that Bogen’s son and son--in--law were expected to eventually assume control of the company.

In 1953 Sidney Harman and Bernie Karmon left Bogen to start their own company. They named the company Harmon/Kardon. Each of the partners contributed $5,000 to capitalize the business at $10,000. The initial product line was to consist of high fidelity tuners and amplifiers. The company began its life , “ in a loft in an old industrial building in downtown New York.” Later the plant was moved to Long Island.

Harmon/Kardon’s first product was an integrated receiver, the Festival D1000. At the time of Harman’s death in 2012, one reporter for the Audiophile Review had this to say about it ( Stone, 2012):

“I’ve read some accounts that claim the D1000 was the first receiver – an integrated amp with a built--in radio tuner, but that was not the most revolutionary part of the design. The Festival D1000’s cosmetics were what separated the D1000 from other manufacturers’ gear, because Harman, aided by his first wife who was an interior decorator, had discovered that consumers buy sound equipment with their eyes .. The D1000 was the first piece of audio gear that was available in more than one front panel finish… (In) 1953 this was huge.”

Reporter Steven Stone then added the following opinion:

“ Although old--time audiophiles will tell you that Sidney Harman’s biggest contribution to audio was hiring Stu Hegeman as his head designer in the late ‘50’s, and allowing him to produce the Citation line of tubed electronics, I believe that incorporating a strong visual style element into electronics was Harman’s biggest and most far--reaching ‘ new idea,’ which is still felt in the industry today. Companies such as Meridian, Levinson and Krell owe much to Sidney Harman and his Festival 1000.”

Harman had little time to sit back and enjoy the success of the D1000. As he explains in his autobiography ( P. 8):

“ In 1955 we took another major step when I judged that the world of single--channel nonaural sound was coming to an end and that the new world of monaural sound was about to emerge. Virtually overnight we abandoned a carefully developed new monophonic product line and created a totally new series of stereo amplifiers – the very first in the industry. They were ready just in time for the 1955 trade

show. Decades later, driven by similar daring, Harman International moved early and decisively from products based on the analog domain to products centered in the developing digital domain.”

The first memorable stereo product produced by Harman/Kardon was the Festival TA230. Reported to be the worlds’ first stereo receiver, it was introduced in 1958 ( Harmon/Kardon, 1/2/12)

The competitive situation pitted the existing large manufacturers of radios against the newly emerging pioneers in the market for high--fidelity tuners and amplifiers. Here is how Sidney Harman described the situation ( Harman, pp.31--32):

“ It was the heyday of radio, and the big manufacturers in the field were RCA, Magnavox, Stromberg-- Carlson, Philco, Columbia, Capehart and Admiral. Each of them produced living room consoles – large pieces of furniture that housed a radio, a record player and a speaker …The reaction of the ‘big boys’ to the arrival of the enterprising high fidelity manufacturers was disdain … We, the high--fidelity makers – Harman/Kardon, Fisher, Bell,Marantz, Jenn, Rek--o--kut, Acoustic Research and Radio Craftsmen – were upstarts. Among us there was very little sophisticated business management and little experience directly related to what we were doing. Some had worked in amateur radio or in conventional radio and television retailing, but for the most part we were drawn to the effort in much the way innocents had joined the gold rush. For all of us, on--the--job training was a necessity. For me, that training was substantially facilitated by two relationships that would endure for a lifetime. Jack Berman was the brightest man in the industry, and Ken Prince was its legendary attorney.”

Much of Sidney Harman’s time was spent on marketing. In order to sign up dealers for Harmon/Kardon equipment, he travelled extensively, visiting, “ virtually every town that had a population of ten thousand or more, trying to persuade existing firms to enter the high fidelity business.” He produced and promoted high--fidelity shows aimed at both potential trades people and consumers. He was particularly proud of Harmon/Kardon’s creative approach to exhibiting at those shows ( Harman, pp 33--34). And he became active in the industry’s local trade association, even serving as its chair

A major breakthrough for the company occurred in 1955 when Harman/Kardon exhibited its first product line at the Radio Manufacturers Association Show in Chicago. It was there that the Allied Radio company discovered Harman/Kardon. At that time Allied Radio was the “dominant market of radio parts, ham radio, hobbyist electronic kits and public address equipment.” (Harman, p.35). Here, in Harman’s words, is the significance of that meeting ( Harman,pp. 35--36):

“ (W)e lit the place up. The senior managers of Allied Radio came by to congratulate us. They were interested in carrying our lines…A lengthy negotiation followed, during which I resisted what I thought were Allied’s excessive demands…We finally agreed that our line would be featured in two full--color pages in the Allied catalog. For the first time, our products would be introduced to a wide audience. We were on the way.”

There was another tipping point factor which accounted for the firm’s success in those days. As explained by Harmon, “ Those early years established Harman/Kardon as a cult brand. The college

campuses were the breeding grounds for a generation who loved the music, and felt that the best way to listen to it was in the dorm with our equipment. Harmon/Kardon was the symbol of the hip, the mark of the congnoscenti.” (Harman, p.36)

In writing his memoir, Harman shed some light on the “gestalt” behind Harman/Kardon’s success with these words ( Harmon, pp.36--37):

“ I loved building a business. What could be better? The products were wonderful. They employed technology wisely. They made beautiful music. My instincts for marketing – for selling, for emotive advertising – was not only indulged, but rewarded.”

“Everything worked. I loved music and found it was everywhere in my life. I loved writing, and found it essential to running a business. I imagined immense possibilities and helped provoke them. I encouraged my people and they rewarded me. I paid attention to the details and that attention paid off in spades.”

While Harman loved the frenzied business life, Kardon did not. He decided to retire in 1956. In order to raise the funds to buy out Kardon , Harman took the firm public in 1956.

JERROLD CORPORATION – JERVIS CORPORATION--HARMAN INTERNATIONAL

In 1962 Harman/Kardon merged with Jerrold Electronics, a pioneering firm in the new cable TV business. The new firm was named Jerrold Corporation. Milton Jerrold Shapp was named chairman and Harman became the president. The idea of such a merger had been proposed by the head of Jerrold Electronics, Milton Shapp. Harman saw the proposal as a significant growth opportunity and enthusiastically agreed. That was due in part to the fact that Shapp wanted to disengage himself from active management in order to run for the U.S.Senate. Harman expected that he would be running the company without much interference from Shapp. While the plan appeared to provide for a harmonious partnership, the two men took the precaution of writing a buy--sell agreement in case it turned out they had irreconcilable differences. The agreement required both to submit a bid for the company with the high bidder buying out the other.

It turned out that the two couldn’t get along. Harman divided the blame between the two. In his words (Harman, p.38):

“ The honeymoon did not last very long. Milton had a way of swooping in without notice, pronouncing his strong views on many business matters. I found the interventions troublesome and inadequately considered … As I reflect on it now, I realize that we were both in error –he for a quixotic, even whimsical approach to running the company; I for lack of patience, forbearance and empathy. He was, after all, the founder of Jerrold, and a genuine industry pioneer.”

To resolve the conflict the two turned to the buy--sell agreement. Shapp made the higher bid. Harman took the money and, newly unemployed, “ drove to the Berkshires to spend a weekend at a small, quiet, family hotel.” (Harman, p.38).

Harman quickly reentered business by investing in the Jervis Corporation. Jervis was a small public company headquartered in Long Island with operating facilities in Grand Rapids, Michigan (manufacturing jet engine components) and Bolivar, Tennessee (making side--view mirrors for automobiles). Harman became actively involved in Jervis. He increased his investment in it; took control; changed the company name to Harman International and sold the Grand Rapids part of the business. A few years later Jervis repurchased Harman/Kardon from Jerrold.

In 1969 Harman acquired a leading manufacturer of high--fidelity speakers, the James B. Lansing Company. In Sidnewy Harman’s opinion that acquisition made a statement that Harman International was, “reclaiming a leadership role in the audio business.” ( Harmon,p.39). There followed seven years of sales growth which took the company’s annual sales volume to over $135 million in 1976.

Perhaps the best--publicized development during that period was the quality of work life program at the company’s Bolivar, Tennessee plant. It was conceived and implemented by Harman himself. His actions were based in large measure on a concurrent experience he was having as president of a Quaker college. Here is a capsule summary of that story told by Harman from the perspective of what he was experiencing as president of Friends World College ( Harman, pp.78--79):

“Although I believed that I was supervising an important experiment in American education, I failed to recognize that, at the same time, in my business life I was running a traditional, autocratic, top--down company. .. All that changed dramatically because of a disruption at our Bolivar, Tennessee plant… (which) manufactured remote--controlled side view mirrors for the automakers… Our plant was aging and old--fashioned. Its employees were mostly black, and it was organized by the UAW. The rates of alcoholism, suicide and drug addition were among the highest in the country…”

“One day at the plant, during the second shift the buzzer signaling the long--standing 10:00 P.M. coffee break failed. …Management determined that it would reschedule the coffee break for ten minutes later… It was at that point that an uneducated, elderly black man … (named) Nobi Cross changed my life…When he learned that the break was to be rescheduled, Nobi Cross stopped buffing and spoke up. ‘ I don’t work for no buzzer,’ he said.’The buzzer works for me.’ In his own way Nobi was declaring that the purpose of technology is to serve the user – not to intimidate or control him. He understood that the only purpose of the buzzer was to announce when it was 10:00 P.M. Since he had a watch he needed no further assistance. And so, when it was ten o’clock, Nobi Cross, followed by his co--workers, walked to his coffee break. “

“ All hell broke loose at the plant. Workers don’t take it upon themselves to determine when they take a break. The managers quickly suspended everybody involved.”

When word of the incident reached Harman in his Long Island office, he contacted his doctoral dissertation advisor (an expert in social psychology) and a United Auto Workers official to plot a course of action. The three immediately visited the plant to talk with the workers about the situation. It became clear that the quality of work life at the plant was abysmal. Harman concluded that the situation could be turned around by creating a learning culture and a feeling of community at the plant. It was an approach something similar to what Friends World College was doing under his leadership.

A school was started at the plant. “The emphasis was not on improving skills, or on teaching old workers new tricks. Instead our school taught what some people within the company knew about and could teach and what some employees wanted to learn, “ said Harman. “ There were classes in English and fundamental mathematics, classes in health and music.” ( Harmon, p. 82).

A company newspaper was started for the purpose of encouraging employees to write about their families, their feelings and their aspirations. “Supervisors were encouraged to share their knowledge and responsibilities with the line workers.” ( Harman, p.84). Production line workers were given authority to stop the line if they thought quality was falling. “ As trust in management grew and as responsibility was delegated to the production workers, their self--respect grew, they assumed more responsibility, and the plant became more productive. Alcoholism, suicide and drug addiction at the Bolivar plant virtually disappeared…Some of those energized employees ran for election to the Board of Education, others for political office. As the plant was transformed, the families and the community were transformed.” (Harman, pp.84--85).

The Bolivar story had a sad ending. As reported by Bloomberg.com, “ The so--called Bolivar Experiment…gave workers the power to make improvements in procedures and to go home when their production quotas were filled, a system called ‘earned idle time.’ In the end that shortened--workday perk created tensions among employees and between workers and managers, according to an article in the New York Times. Harman sold the factory in 1976, and subsequent owners let the experiment expire.” ( Arnold, 2011).

For Sidney Harman, however, Bolivar left a lasting impression. In his words ( Harman, p.85):

“ The Bolivar experiment has shaped my approach to business for more than thirty years. I have applied its principles everywhere, and although the results have varied and some of that sense of youthful, romantic enthusiasm has been difficult to replicate, the practices have led consistently to higher productivity and widespread respect for those who do the work.”

The publicity generated by Harman’s quality of work life endeavors made him known and admired by U.S. vice presidential candidate Walter Mondale who recommended him to president--elect Jimmy Carter. In 1976 Harman accepted Carter’s invitation to serve as Deputy Secretary of Commerce in the Carter administration. To avoid conflicts of interest Harman sold Harman International to Beatrice Foods, a prominent conglomerate at the time. Beatrice had previously approached Harman about an acquisition.

Harman worked for the Carter administration for two years before returning to private life. In 1980 Harman was presented with an opportunity to repurchase his old company from Beatrice. As he explained the situation ( Harman, p.41):

“ (W)ith government service behind me, I was approached again by Beatrice Foods. Their adventure as a conglomerate had been disastrous… Harman had done especially badly. Beatrice was in turmoil and under enormous pressure from their banks and shareholders. No one at Beatrice understood the high-- fidelity business, no one had any affection for it, and the people at Harman were demoralized. Beatrice

needed me … Beatrice was prepared to finance the acquisition if I would take it off their hands. I did that with only a modest commitment of my own funds. Years later , I realized that the transaction had been one of the first in America’s love affair with the leveraged buyout – the use of heavy debt, instead of hard equity, to make acquisitions.”

Sidney Harman had sold Harman International to Beatrice for about $ 100 million. He bought the company back from Beatrice for $ 55 million. Under Beatrice the value of Harman International’s assets had fallen by about 40 percent. ( harmankardon.com).

Harmon/Kardon was not part of the business which Sidney Harman bought back from Beatrice because Beatrice had previously sold Harmon/Kardon to a Japanese investor. However, in 1985 Harman was able to buy Harmon/Kardon back from the Japanese owners. ( HarmanKardon.com).

As the new controlling stockholder in Harman International, Sidney Harmon, “ had no large vision for the company, no master plan”. He just, “ wanted to keep busy and perhaps make a living.” However, as he wrote in his autobiography, years later, “ I did instill my personal values about hard work and personal integrity; and my determination that Harman International would be an honorable company. I thought I would stay for five to ten years.” (Harman, p.42).

A significant element of Harman’s growth strategy in the 1980s was the acquisition of small companies with good brand reputations but financial problems. Among those acquired were Infinity (1983), and Harman/Kardon (1985). In the case of Harmon/Kardon, the business was not included in the 1980 buy--back from Beatrice because Beatrice had already sold it to a Japanese company.

Throughout the 1980s Harman struggled to find a chief executive or chief operating officer with whom he could work effectively. The company was struggling and he wanted to be actively involved in turning things around. But neither of the two men chosen during that decade was able (or willing) to work with him. “ I began to wonder whether I could make it work with anyone,” writes Harman in his autobiography. “ I could develop no traction in the company and felt too far removed. Each time I wished to talk with key people, they seemed to be in a meeting. I became convinced that the company would drown in meetings.” ( Harman,p.42).

Finally, in 1992, Harman found a new partner with whom he could work effectively, Bernie Girod. Girod was made chief executive while Harman assumed the position of chairman (changed to executive chairman in 2001). (Arnold, 2011).“ While he and I have totally different personalities and different strengths,” said Harman, “ I was now inside and leading and I had a genuine partner. And our relationship has grown stronger over the years. The meetings ended, the army of consultants disappeared, and we got to work.” ( Harman, pp.42--43).

Growth in the 1990s was also based in part on acquisitions. Two key acquisitions which were related to automobile customers were Cleveland Electronics and Becker Radio. In the case of Cleveland Electronics ( Harman,pp.43--44):

“ Serendipity brought me to Cleveland Electronics …located in Martinsville, Indiana. Cleveland Electronics was a subsidiary of the Essex Wire Division of United Technologies Corporation (UTC) .. The firm manufactured loudspeakers for automakers. They were commodity products … Not once in the years of UTC’s ownership had anyone from the Essex office in Dearborn visited the plant. All management, marketing and engineering resided in Michigan…(T)he employees’ spirits in Martinsville were bleak. The day we closed the acquisition, we changed the name to Harman--Motive, and I showed up to assure everyone that we would transform the place..Since that day, I have been to Martinsville many times. Today it is known as Harman/Becker, and the plant produces Harman--branded music--reproducing systems for the major automakers. It is a state--of--the--art facility, bright, clean and superbly equipped with medical services and a gymnasium on site.”

In the case of Becker Radio ( Harman, pp .45--46):

“ In 1995 we bought the German company Becker Radio, pretty much on the way to its funeral. Becker had been founded fifty years earlier by Max Egon Becker. The company manufactured radios for Mercedes Benz and was, for much of its history, one of Mercedes’ unofficial children…But when the Japanese auto companies began to gain market share in the luxury category, Mercedes recognized that it could no longer succeed in the old, patriarchal way…To its credit, Mercedes changed. But sadly, the old Becker could not. It fell into decline and was threatened with bankruptcy when the banks forced it to present itself for sale. After an intense competition among a dozen suitors, Harman acquired it for a modest amount of cash and stock and the assumption of debt.”

Harman successfully turned Becker around. Equally important, Becker provided Harman with a vision for the next generation of audio products. As explained by Harman ( p.47):

“ Shortly after the acquisition I visited one of two Becker factories in Germany’s Black Forest. There, a small group of newly enthused engineers had set out a remarkable display. On a table fifteen feet long and five feet wide they place the analog equipment… Then, on a table less than one--quarter that size, the engineers had placed boxes representing the digital equipment that would provide the same functions… It did not require a genius to recognize that I was looking at the future. When I returned to the States, I told Bernie Girod that we had, ‘better find us a digital engineer.’ Today we have twelve hundred digital engineers in the company.”

In 2012 the official Harmon/Kardon web site looked back on the 1990s and offered the following assessment ( harmankardon.com):

“ Returning to Harman’s hands didn’t suddenly make Harman Kardon a flowering success. In the 1990s Harman Kardon was running into trouble. The company still made excellent products, but it wasn’t leading the industry in new technologies anymore. The world of audio no longer spoke about hi--fi and stereo but about CDs, MP3, DAT, and other bits of technology.”

“Harman, his executives and his engineers took action. In 1999, for instance, Harman Kardon presented the CDR 2, the first CD audio recorder…Also that year the company produced SoundSticks® computer

speakers, a combination of science and sculpture so beautiful that New York’s Museum of Modern Art has added them to its design collection…”

“Additional inventions followed. By 2003, the company’s 50th anniversary, Harman Kardon was going strong again.”

Sidney Harman continued to run the company until May of 2007. A month earlier Harman International had agreed to a sale to an outside group assembled by Kohlberg Kravis and Roberts and Goldman Sachs Group for about $ 8 billion. That deal fell through several months later. ( Laurence Arnold, 2011). Harman was succeeded by Dinesh Paliwal. A successor manager search had brought Paliwal to Harman ( from the presidency of the global power and automation technology leader ABB) in 2006. In 2007 Harman International had $ 3.55 billion in sales; a net profit margin of 7.8 %; and a Value Line projected annual rate of growth of the price of a share of company stock at between 18% and 28% between the end of 2011 and 2014--2016 ( based on the report of October 7,2011).

Sidney Harman died of leukemia on April 12,2011. At that time Harman International

CONCLUSION: MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES AND PHILOSOPHY

The best way to become familiar with Sidney Harman’s management principles and philosophy is to read his autobiography, Mind Your Own Business. Among the beliefs presented there are:

1. Purpose of the business -- Harman believed in the “stakeholder” view. Management’s job was to draw on the full resources of the stakeholders to achieve high rates of productivity growth, quality improvement, innovation and quality of work life. The rewards of doing that successfully were to be shared with all stakeholders – employees, investors, local communities and government.

2. Business--government relations – In his mature years Harman rejected both the so--called liberal and the so--called conservative views of business government relationships. Instead he subscribed to an ideologically free approach to the issue. In his 1988 book he addressed the problem of American economic competitiveness in the new global economy. He and his co--author, Daniel Yankelovich argued that competitiveness could be restored by using what the two authors called the “more--for--more” strategy . One of his many statements of this mature view was ( Harman, 1988, pp.228--230): L yndon Johnson’s Great Society assigned a central role to government, giving priority to communal values. Reagan conservatism swung the pendulum in the opposite direction. .. In the post Reagan era, it is likely that a more positive role for government will be reconstituted., but that it will be in keeping with the more--for--more principle of giving priority to market values (which means that government’s role, although important, will be secondary to that of the private sector).”

“As government shifts from its regulatory and welfare--state role of the 1960’s and 1970’s to a supportive role for industry, it recognizes that the main player in revitalizing American competitiveness must be a private sector as free as possible from regulations and constraints. But the public sector helps to create the conditions that will assist the companies to become more competitive and to insure that the communal values in the national interest are well represented. The conservative assumption that the sum of all individual market decisions will automatically serve the national interest ( the ‘invisible hand’) is not borne out by experience. Many business decisions give too much weight to short--term considerations whose effect may be to undercut that interest ( for instance, decision--making to produce in other nations, to skimp on research and development, to neglect the skill level of the work force, and to sacrifice other values important to the community).”

3. Personal compass – Here is how Harman addresses this matter in his autobiography (Harman, 2003, pp. 164--165)

“ I choose fairness and personal development – my own, my colleagues’ and my constituents – over personal financial enrichment. I judge that something is good or bad depending on whether it supports those objectives. I have persuaded myself that if I pursue such a path, I will successfully and constructively fulfill my obligations to the shareholders, stakeholders and investors in our business, my family – and myself.”

4. Harman International’s governance structure – In his early years as an entrepreneur Sidney Harman managed with a pyramidal governance structure. But after his experience with the Bolivar plant he changed to a much more team--oriented approach. That approach applied at all levels, from top management to the production line. One reason Harman often gave for that change was the fact that different employees bring different talents to the work place and better decisions and actions result from utilizing all of those talents. A second reason Harman often gave was that the successful performance of more and more jobs was becoming dependent on giving the individual worker more discretion. In his words, the American corporation had been succeeding with a “low discretion” workplace but in the new world of global competition success required corporations to create “high discretion” workplaces. This topic is most extensively explored in his 1988 book.

5. Jazz as a metaphor for Harman’s top management operating process – Harman was fond of using jazz as a metaphor for thinking about how to create successful high discretion workplaces. Here is one example of that ( Harman, 2003, p.12):

“ The relatively easy part of running a business, I have found, is creating budgets, exercising business controls, managing cash flow. The tough part is negotiating the interplay of personalities and helping them work together effectively. How the leader deals with the temperamental employee who responds to every question or challenge as a personal rebuke, and with the seasoned veteran who strives to keep others at arms length, is the hard part.:

“ I am proud of the fact that although the four top executives at Harman International could hardly be more different, they have melded into a virtuoso jazz quartet. I do not claim that I have melded them. I have come to see that the best role for a leader is, in fact, to serve as ‘first among equals,’ and in that capacity the leader must contribute to that meld. If he is good, he encourages and helps catalyze similar contributions from his colleagues. ..”

“ Our organization is fueled by the nonlinear, multidimensional energy of the group. Although each member brings special and different skills to our work, each encourages the other to be interested in and competent in his specialty…”

“ I am baffled every time I encounter a company working in the world of digital technology but operating and managing in a traditional, top--down, linear – what I call analog – fashion. It makes no sense to run a digital operation with old--fashioned analog management.”

6. Importance of mastering the basics -- It would be a mistake to think that Harman’s “jazz as a metaphor” approach to management fails to give appropriate attention to mastering the basics of business. Harman did believe that mastering the basics was easier than mastering interpersonal relations. But he also believed that the mastery of the basics was crucial for business success and that far too many businesses lost their competitiveness by failing to master the basics and continuing to maintain that mastery.

7. Quality of work life as a strategic asset – Beginning with the epiphany of the Bolivar incident, Harman became convinced that top management had a responsibility to create a high quality of work life for all employees and that success at doing so would create a strategic asset.

8. Managing technology – Continuous improvement through new technology was seen by Harman as an important management goal. But he warned against letting technology dominate management thinking. As he once put it in his autobiography, “ (W)e must not subordinate intelligent management and marketing to technology. Technology must never be permitted to tyrannize. It must be the servant of the client. …Many catastrophic business decisions have arisen from the view that the engineers know best; if a new product could be built, that was reason enough to go forward.” ( Harman, 2003, p.9)

9. Labor unions -- In 1988 Harman presented a vision of a “winning strategy” for American firms in the new global economy. He called that vision the “more--for--more strategy. Here is his view of the role of labor unions in a that high productivity, high product quality, high quality of work life strategy ( Harman, 1988, pp. 250--251):

“ The more--for--more strategy calls for a new role for organized labor. … (T)he future depends to a great extent on how effectively organized labor functions. Without the unions there is no

effective bargaining representation; it is left to management to determine what is fair. Generally, managements of companies change more frequently than managements of unions, and there is no assurance that the new managers will endorse the more--for--more approach. It is the unions that may offer the best promise of continuity.”

“ In the more--for--more strategy, organized labor has several important roles to perform. The main function of trade unions in the past has been collective bargaining. This will continue to be central in the future, but under vastly different circumstances. These include:

• the recognition that in a high--discretion workplace the individual becomes more important and individual differences in performance and rewards may be decisive in competition:

• a less adversarial relationship between labor and management in the pursuit of a common interest;

• the need for unions to possess greater knowledge of the management side of the picture and to assume more responsibility for the fate of the business;

• less rigidity with respect to work rules, and a much greater concern with productivity;

• a welcome rather than a rebuff of pluralistic forms of reward and pay for performance, with less sacredness attached to seniority;

• less emphasis on national bargaining and more on local, company--by--company agreements;

• greater responsibility for the education and training of members; and

• a greater responsibility for shaping national policy, not as a special interest but as a representative of the overall health of the economy

“ If there ever was a time for a fresh start in the trade union movement, it is today. If unions persist in supporting the old, discredited adversary relationships with employers, and most particularly in retaining the structured, autocratic organizations of the past, they are doomed to loss of membership. Unions will determine that they must become models of participation and of democracy in action if they are to play a central role in the new framework.”

10. Mavericks -- The sub--title of Harman’s autobiography is , “ A maverick’s guide to business, leadership and life. Here is what he meant ( Harman, 2003, pp. 3--4)”

“ There is the traditional way to conduct business and do your job, as for the most part it is taught in the business schools and practiced in industry. There is a deeply flawed New Economy way. And there is the maverick’s way that looks not to the dogma of the past, nor to existing models of action and behavior, but struggles to determine what is truly effective regardless of traditions and trend …”.

“ The maverick’s way of conducting business forswears the leader as commanding general; it rejects the practice of top--down, authoritative command. Rather, it proposes the leader as catalyst, conscience and inspirer. It embraces technology, but only in the service of the customer, not to his intimidation or for its own sake. It sees that much of what ails business today arises from the narrowness of preparation, the emphasis on specialization, and the failure to build a philosophical base or sound judgment based on critical thinking. Critical thinking allows one to review business decisions against a carefully developed, carefully honed set of personal values.”

CONCLUSION

REFERENCES

Alter, Jonathon, “Sidney Harman: An Extraordinary Life,” The Daily Beast, April 13, 2011.

Arnold, Laurence, “ Sidney Harman, Who Built a Fortune in High--Fidelity Stereos, is Dead at 92,” Bloomberg.com, April 13, 2011

Chavez, Paul, “ Remembering Sidney Harman,” Venicepatch.com, ________________

“Harmon Kardon History,” harmankardon.com/EN--US/AboutUs/History/Pages/History.aspx, accessed 1/2/2012.

Harmon, Sidney. Mind Your Own Business. New York: Doubleday, 2003

Harmon, Sidney and Yankelovich. Starting with People. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1988.

“ In Memoriam: Sidney Harman, 92”. USC News, April 13,2011.

McFadden, Robert D., “ Sidney Harman, Newsweek Chairman, is Dead at 92,” The New York Times, April 13, 2011.

“Sidney Harman”, www.reference.com/browse/sidney+harman

“Sidney Harman (War Profiteer) dies at 93” www.youtube.com ,accessed 1/2/2012.

Stone, Steven, “ Thoughts on Sidney Harman,” audiophilereview.com, accessed 1/3/2012

APPENDIX: THE REST OF THE STORY

EDUCATION, ART, MEDIA AND CHARITY

Teaching and Mentoring at--risk students in Virginia. In 1955 the United States Supreme Court declared public school segregation to be illegal. Prince Edward County in Virginia resisted by closing its public school system in 1959. A private academy was opened for white students and for four years black children were without formal education. In 1962 Sidney Harman was invited by two friends to join them as teachers in a new school to be opened for blacks in Prince Edward County. As Harman remembers ( Harman, pp. 151--152):

“ For eleven glorious months our school was the Camelot of education. We loved it and the kids loved it. I flew to Richmond at my own expense to teach them. The trip from the airport to the town of Farmville, Virginia where I lodged with a black family, was always harrowing. The car was trailed, bumped, and harassed – and I was often frightened. But the school was wonderful; the classes I taught, and my un--cashed paycheck, stay with me these decades later. One class was in American history, which I tried to teach from the perspective of a black person in the South. ”

One of the friends who partnered with Harman in Virginia was Dr. Neil Suillivan. Sullivan subsequently became superintendent of a school district on Long Island. It was the district where Harman’s four children attended school. So it was no surprise when Harman agreed to serve on the district school board. In 1965 he became president of the school board. (Harman, p. 152).

Friends World College. Harman’s school board background and his position as a successful businessperson led to his appointment to the board of a Quaker college in Long Island named Friends World College. In 1970 he was chosen to serve as the full--time president of the college while still running his business full--time. Here’s how he managed to do that ( Harman,p.77--78):

I would be at my office at Harman International as early as 7:00 or 7:30 in the morning. In the afternoon I would eat a brown--bag lunch while driving myself from the office in Lake Success to the Long Island campus of the college, twenty--five minutes away. Arriving at 2:00 or 3:00 P.M., I would change in the car from my suit to the uniform of academic life, jeans and an open shirt. I was usually there until 11:00 P.M. The days were lengthy and taxing, but the peace and intellectual stimuli filled me with excitement.

Harman spent three years as president of Friends World College. During that time he became familiar with a new educational model, “In which people would be in charge of their own learning.” (Harman, p.154). Two “revolutionary” thinkers behind that model and it

movement were Ivan Illich in Mexico and Paolo Freire in Brazil. Their writings were highly influential at Friends World College and they had a significant impact on Harman. Harman has this to say about his exposure to this new model ( Harman, p.155):

“ The college (World Friends College) was headquartered in Northampton, Long Island. There were centers in seven other countries including Mexico, Great Britain, India, Africa and China … During that three--year period, I spent time at the centers in Mexico, London, India and Africa. Each confirmed the potential in the concept, and in each a number of students wrote stunning journals. The level of original writing exceeded anything I had ever encountered when I was in school. As a student, this was material I had yearned for.”

Higher Education – Aspen, Emory, Harvard and USC. In his later years Sidney Harmon became involved with several university programs. He was the founder and an active member of the Program on Technology, Public Policy and Human Development in Harvard University’s John F.Kennedy School of Government. At the University of Southern California he was a visiting professor and entrepreneur in residence, the first Judge Widney Professor of Business, and the inaugural holder of the Isaias W.Hellman Chair of Polymathy. He was also active in the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies where he chaired the program committee. He was a member of the board of the Carter Center at Emory University. He endowed a writing program at Baruch College.

ART AND CHARITIES. Sidney Harman loved music – both jazz and classical. He served as a trustee for the Los Angeles Philharmonic Association and the National Symphony Orchestra as well as the Washington, D.C. Shakespeare Theater Company. Harman donated $19.5 million to the Shakespeare Theater Company for the building of an expanded facility. The result was the Harman Center for the Arts which opened in 2007.

PUBLIC AFFAIRS AND NEWSWEEK. Harman had a strong interest in public affairs. At one point in his career he took time to express his views on national defense and economic competitiveness in a book coauthored with Daniel Yankelovich ( Harman, 1988).

Harman was chairman of the executive committee of the Board of the Public Agenda Foundation; a member of the Council on Foreign Relations; and a member of the Council on Competitiveness. He was a founding member and chairman of the Executive Committee of Business Executives for National Security. That last affiliation attracted emotional attacks from opponents of U.S. involvement in wars ( “Sidney Harman (War Profiteer) Dies at 93). That was ironic since Harman strongly opposed the U.S. war in Vietnam.

Near the end of his life Harman attempted to rescue an old--line public affairs magazine. As summarized by Laurence Arnold, “ Last August, Harman agreed to buy Newsweek from the Washington Post Company ( WPO) for $1. Winning a three--month bidding process for the money--losing publication. Donald E. Graham, chief executive officer of Washington Post, said Harman was chosen because he ‘feels as strongly as we do about the importance of quality journalism.’ In November, Harman and Barry Diller, owner of The Daily Beast , agreed to a merger with Daily Beast founder Tina Brown serving as editor of both publications. “ ( Arnold).

GOVERNMENT SERVICE

Harman’s initial job as Deputy Secretary of Commerce was to staff the senior positions in the Department of Commerce and to serve as chief operating officer for the department’s more than sixty thousand employees. Soon after assuming office, Harman became involved in an instructive experience involving the competitiveness of American show companies. Here, in part, is how he tells that story in his autobiography ( Harman, pp. 158--160):

“ The shoe industry consisted for the most part of small, privately held companies with annual sales in the $1 to $10 million range. Typically they were run by second--or third--generation descendants of the family founders and were located in now fewer than thirty--two states. … When the industry found itself in deep trouble because of rising competition from Singapore, Korea, Indonesia and Italy,… the principals in those companies came to see me. They wanted trade embargoes and border relief… I learned quickly that some of the small companies knew how to make a very good product, but had absolutely no idea how to cost or price it. Some knew how to make it and how to price it, but were bereft of any ability to market and sell it. There were many who knew how to do all of that, but were totally incapable of manufacturing in a reasonably efficient fashion. I identified the approximately 150 troubled firms and assembled a dozen teams from different departments of government ( each included a marketing person, and accounting specialist, and a knowledgeable production person)… The program worked remarkably well … So successful were we that when the Reagan administration came to town four years later, it announced that we had done our job. The old--line shoe industry had been revived and the program was no longer necessary. It was dissolved…I thought that judgment was incorrect.”

FAMILY

Sidney Harmon’s first marriage was to Sylvia Stern. That marriage lasted 25 years and produced four children – Lynn, Gina, Paul and Barbara. The couple divorced amicably because of emergent lifestyles which were incompatible. In Harman’s words, “ We were unable to overcome the tension and pressures in our marriage generated by my 24/7 days … running Harman International and Friends World College … We maintained a cordial relationship..until, sadly, she died.”

Following the divorce Sidney was a bachelor for ten years before marrying Jane Lakes in 1980. He met her through his work as . At the time she was a lawyer working as deputy secretary of the Carter cabinet. with the U.S. Department of Commerce. She was 25 years his junior and she and Sidney had two children – Daniel and Justine. With Sidney’s support she subsequently ran for public office and served in the U.S. House of Representatives. She also ran unsuccessfully for the governorship of California. ( (www.nytimes.com/2011/04/14)

This article was written by Dr. Richard Hattwick.

ANBHF Laureates

Our laureates and fellows exemplify the American tradition of business leadership. The ANBHF has published the biographies of our laureates and fellows.

Some are currently available online and more are added each month.