QUAD/GRAPHICS

(This profile is based primarily on John Fennell’s in-depth biography of Harry Quadracci – Ready, Fire, Aim)

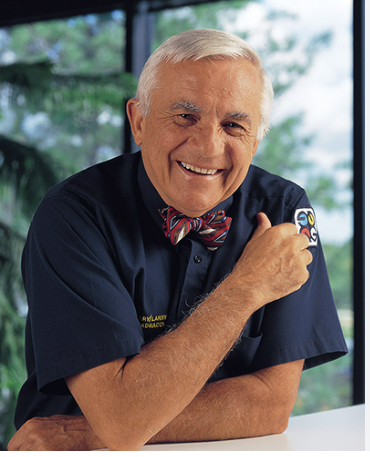

Harry Quadracci was a successful upper level manager at a leading American printing company when a labor union negotiation undermined his chances to become company president. He resigned and started his own printing company. He designed the new company around innovative new principles. After a shaky start the company grew into one of America’s largest and most innovative printing businesses.

I. YOUTH AND FAMILY BACKGROUND

Harry was born in Racine, Wisconsin on June 10,1936. Six years earlier his father, who , at that time, was 16 years old and still in high school, bought a letterpress and opened a small printing business in the family garage in Racine, Wisconsin. The father, also named Harry, continued that business after graduation. In 1934 the father sold his press to a Milwaukee entrepreneur, William Krueger, and joined Krueger in his new printing venture as the company’s first employee.

When Harry (junior) was eleven years old his family moved to Milwaukee. By that time Krueger was a successful company with 100 employees and Harry’s father was a top Krueger executive.

In Milwaukee Harry attended a Catholic grammar school and then the Jesuit-run Marquette high school for boys. After high school Harry enrolled at St. Regis College in Denver, Colorado.He majored in philosophy with minors in psychology and English. ( St. Regis was a Jesuit founded school. Harry earned As and Bs except for four Cs, two of which were in accounting.

II. SHORT-LIVED LAW CAREER

After graduating from St. Regis Harry entered the Columbia University la school. (He originally planned to attend a Catholic university to study law but was told by an advisor that he had had enough Catholic education.( Fennell,P.32)).

Harry graduated from Columbia University in 1960 and worked for one of Columbia’s law school professors while preparing to take the New York bar exam. After passing that exam he interviewed with various New York law firms but received no offers of employment. He also failed to land an offer from a Milwaukee law firm. But he did receive a promise of outsourced work from his father’s company, W.A. Krueger. The offer was made by the company’s new president, Robert Klaus. So Harry moved back to Milwaukee where he did work for W.A. Krueger and also for several other clients.

III. WORKING AT W.A. KRUEGER

Harry impressed the president of W.A. Krueger and after a year of doing legal work for the firm he was offered a full time-job as Krueger’s director of industrial relations in 1962. Harry worked at Krueger for the next seven years. He progressed rapidly there. In 1963 he was appointed secretary of the company. In 1966 he was named manager of the Brookfield plant. In 1968 he became general manager of the Wisconsin division and a vice president. By then he was being considered as the possible next company president. That possibility was in no small measure due to the growth of his division, his energy, his mastery of seemingly every aspect of the business, and to his popularity with the employees. As biographer John Fennell puts it ( p.41):

“Harry put himself in the middle of the action. Rushing from one end of the plant to the other solving whatever problem developed, he was a bundle of energy “

“ Harry put much of his efforts into improving the work lives of Krueger’s employees, believing that companies with content, loyal workers are more productive, leading to efficiencies and higher profits. He took special interest in people who showed promise, helping direct their careers. He immersed himself in every detail of the company and got involved in the lives of many of its workers. Knowing he listened sympathetically, employees lined up outside his office.”…

“ If Harry thought the salary for a particular job was too low, he raised it. But when he recruited shop employees for management positions he almost always paid them less than what they should have earned in exchange for the chance to rise. It was a pattern he continued throughout his career.”

Harry’s chances to become president disappeared as the result of a labor strike at the company. The company’s union made demands that management could no’t agree to and in response 290 of Krueger’s 900 employees walked out. It was the first strike in Krueger’s history and the action devastated top management which thought employees were more loyal. Harry was in charge of the subsequent negotiations with the union and he tried to break the strike by keeping the presses running. That strategy was no’t working. The company president stepped in and negotiated a settlement ( “behind his back” thought Harry); Harry concluded that his chances to become the company’s next president were gone. He decided to leave Krueger and start his own printing company.

A year after he started work at Krueger, Harry married Betty Ewens. Theirs was a long and complicated “courtship”. But the end result was a marriage that was deeply 3 fulfilling for both of them and, possibly, one of the underlying keys to Harry’s later success.

When Harry decided to leave Krueger he put his family in a difficult position. In addition to Betty he had three children to support. He didn’t have much savings to draw on. He knew that he would have to find an interim job until he could get his new company off the ground. But Betty encouraged him to make the move and so on Christmas Eve, 1969, he left Krueger.

IV. STARTING QUAD/GRAPHICS

As expected, Harry spent the next year working as a consultant. He did work for a Chicago printing company and served as acting president of a small Detroit printer. He usually stayed in Detroit three or four days a week. During that time he looked for a printing company he could buy. But nothing materialized. Finally, in the fall of 1970 Harry and Betty agreed that he should try to start his own company.

Harry sketched out the elements of a business plan and took it to a young attorney named Alvin Kriger. Harry had been introduced to Kriger by Betty’s cousin and investment banker, Irwin “Win” Purtell. The basic business model that Harry explained to Kriger was a nonunion company printing color newspaper inserts using a new web offset press. Web offset printing was about to trigger a boom in print advertising. But few industry incumbents realized that at the time. Most printers still used letterpress. And that, thought Harry and his father, created a unique opportunity for new printing firms. (Fennell, p.61).

Kriger agreed to put the vision into a formal business plan . Included in the plan would be a proposal for two classes of investors, one to provide the operating capital at $2.50 a share and the other to provide financing for the new press ( which cost $850,000). Financing the press was expected to appeal to wealthy investors because of the tax credits that were involved. ( Fennell, p. 51).

Harry, Kriger and Win Purtell then set out to find investors. It was a tough sell. Harry and Betty finally decided that Harry should quit his other work and focus on fundraising. That put them in such a bind that Betty prevailed on her family to cover her family’s living expenses until the business had been started. Then, every so slowly, investors began to trickle in as friends invited their friends to invest. Harry’s ability to tell his story was an important part of that one-by-one process ( Fennell, p.62). Eventually $475,000 had been raised and the First Wisconsin Bank agreed to finance the rest. On July 13,1971 the papers were signed incorporating Quad/Graphics as Harry called the new firm ( Quad standing for Quadracci and Graphics for the business the firm was in). Harry and his family controlled 60 percent of the equity ( Fennell, p.56).

Harry then leased an empty 20,000 square feet building in Pewaukee, Wisconsin; ordered the new press; and under the direction of his father had it installed in the fall of 1971 ( a nine week process). Even before the press was installed, Harry picked up a 4 pressman, Jerry Kreuzer. Kreuzer had worked for Harry at the Krueger plant; had crossed the picket line during the strike at Krueger; and was so unhappy at Krueger that he resigned and came to work for Harry. Their agreement was that Kreuzer would work without salary until Quad/Graphics was up and running. The date of that first hire was June 1, 1971.

Once the company was up and running Harry added additional workers, most of whom were known to him from his years at Krueger. Among the new recruits was his father who joined his son in 1972. That move had special significance for the future of Quad. As reported by Fennell ( pp. 557-58).

“ Senior officially joined Quad in January 1972. In years to come, he became the guiding spirit behind Quad’s success, the keeper of its values.’He projected what was good about Quad,’ says his grandson, Joel, now Quad’s president and CEO. ‘ Whether it was pouring a concrete floor or installing a press, he paid attention to every detail’. Esteemed by all because of his experience and technical knowledge, he was the quiet counterbalance to his risk-taking, tempestuous son, always there to answer questions from pressmen, always making sure the day-to-day operation ran smoothly.”

One other new hire worth special mention was John Fowler. Small and precarious as Quad was in the beginning, Harry wanted to be audited by a major accounting firm (to inspire confidence) and hired Arthur Andersen to do the work. Andersen assigned new hire John Fowler to the job in 1974. Fowler and Harry clashed from the beginning but at the same time they came to respect one another. So, when in 1979 the Quad board of directors pressured Harry to hire a chief financial officer, Harry talked Fowler into taking the job. Over the years Fowler would be one of Quad’s most important officers. ( Fennell, pp. 103,106-08).

The next challenge was finding a salesman. Harry ended up performing that job even though he had little confidence in his sales abilities. It took Betty’s insistence that he could succeed because he was such a good story teller and because in this case he would be telling a story about which he was passionate. So off he went to make sales calls and he soon had his first customer, a monthly Wisconsin business magazine named Investor (Fennell, p. 62). His original idea of color newspaper inserts turned out to be ahead of its time. So Harry sought any kind of printing work he could find and Quad/Graphics quickly became a place where other printers placed work they couldn’t handle in their own facilities ( Fennell, p.63).

That, of course, wasn’t the vision with which Harry started the company. Nor was it the vision that attracted many of the early employees. While he might have had his own fears of failure, he exuded confidence that Quad/Graphics would one day be a big success and such was his charisma that many employees bought into the dream. As one of the 5 early employees put it, “ He just radiated assurance that this was going to work. He never let on that there was ever a faint possibility of doubt.” ( Fennell, p.64).

“Harry wanted his plant to be more like a law firm, with partners rather than employees, each responsible for the success of the business. That’s why he also expected those employees who could to invest in Quad. Of the original staff, almost half had a personal financial stake in the company.” ( Fennell, p.64). Harry had a practical reason for sharing profits – he thought owners worked differently and better than employees. But there was something else. Once, when Harry’s brother Tom asked him about his vision for the company, Harry replied, “ I want to make everyone out there on the floor millionaires”. ( Fennell, p.65).

“Along with the ideas of ownership, shared responsibility and trust, Harry insisted there would be no time clocks, no hierarchical structure, no titles, really no rules except to print quality work for clients. During the first year of operation, Harry purchased medical and life insurance coverage for employees and their families. He initiated the policy of fresh uniforms on a daily basis, a benefit he helped start at Krueger.” (Fennell,p.65).

One policy Harry didn’t get right in the beginning was work schedules. At first the work schedule was dictated by the flow of jobs. If a big job came in then crews would work 12 hour days for as long as it took, which could be weeks. The work crews eventually objected so strenuously that a change was agreed upon. Crews would work 12 hour shifts three or four days in a row, if the work load demanded it, and then get three or four days off before the next shift ( Fennell, p.75).

In May, 1972, desperate for jobs, Harry accepted work from a Milwaukee company that printed the men’s magazines Penthouse and Playboy. Then , in 1974 he sought and won the job as sole printer for George Doherty’s two men’s magazines, Genesis and Swank. To Harry these contracts were matters of survival not morality. Later, when Quad/Graphics had enough more respectable business, Harry stopped publishing all men’s magazines except for Doherty’s. That business he retained out of a feeling of loyalty for the way Doherty had helped Quad survive. Even later he picked up the Playboy account and the account for the feminist magazine Ms. Both magazines were printed in the same plant. When Ms magazine publisher Gloria Steinem made a celebrity visit to that plant, she was asked if she objected to having her magazine printed in the same place as Playboy. She replied, “ I think it is only fitting that the same presses that print the poison also print the antidote.” ( Fennell, p.140).

In 1974 the company faced a financial crisis when the First Wisconsin Financial Corporation, holding the $ 600,000 loan to Quad/Graphics, voiced its concern about Quad’s viability and announced plans to put serious restrictions on Harry’s ability to run the company. Harry managed to talk them out of that move. Nevertheless, at the end of 1974 the company was still marginally profitable. It had 35 employees and had done between $3 million and $4 million worth of business that year. ( Fennell, p.73). ‘The firm had made a profit in 1974 and that enabled Harry to pay the company’s first ever bonus 6 to managers. ( Fennell, p.77). In addition, Harry introduced an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) for all employees with 25 percent of profits before taxes put into the plan. By 1976 business had grown to the point where a second press was needed and installed and by the end of that year Quad/Graphics employed about 100 people.

It was then , in the winter of 1977, that Quad/Graphic achieved its legendary breakthrough with Newsweek. Harry had been trying to land a contract to do some of Newsweek’s printing. So when a winter gas shortage caused one of Newsweek’s suppliers in Ohio to shut down, Newsweek took a chance on Quad. Here’s the rest of the story as told by a Newsweek insider ( Whitaker):

“ (O)ur director of printing, Angelo Rivello, called a young entrepreneur from Wisconsin who had started a small printing firm called Quad/Graphics, His name was Harry Quadracci and he took the order. Relieved, we shipped our layouts, but a huge snowstorm forced the plane to land in Chicago. We couldn’t find the parcel, and called Harry in distress. Not to worry, he said: he had sent a car through the blizzard to pick up the film. The magazine was already on press. It was, as they say, the start of a beautiful friendship. We were so impressed by the quality and reliability of Quadracci’s operation that we gave him all of our Midwest business a year later. It was his first big account and he ran with it. During the next two decades Quadracci kept investing in the best new technology –and the best people—and built Quad/Graphics into the largest privately owned printing company in the world, with 11,000 employees, 35 facilities around the globe and annual revenues of $ 1.8.”

That account fails to mention the following additional part of the story. While Quad was fulfilling its contract, Newsweek’s director of printing, Angelo Rivello, was having a tough time getting its primary printer, R.R Donnelley, to agree to immediately print an additional 250,000 covers. So, Rivello switched the order to Quad. Rivello was apparently upset with Donnelley’s inflexibility. As he put it,” The biggest printer in the world couldn’t do an additional 250,000 impressions but we found a small one that could.” ( Fennelly, p.83).

Having made a great first impression, Harry then made it his mission to land more of Newsweek’s business. In numerous calls on Rivello he made a convincing case for Quad/Graphics being able to handle the higher volume. Quad had already convinced Newsweek that its quality was exceptionally high. And he explained how Quad could deal with one of Newsweek’s on-going concerns, one it had with all of its printers, the matter of overtime pay for work done on Sunday. Harry explained that Quad/Graphics didn’t pay overtime for Sunday work. “That was revolutionary,” Rivello later said. “ That idea broke through every barrier there was in the business at that time. No one had done that. No one.” ( Fennell, p. 85)

V. SUBSEQUENT EVOLUTION INTO INDUSTRY LEADERSHIP

With the Newsweek breakthrough Quad/Graphics served notice that it was an agile competitor and one which the larger printing firms had better take seriously. Over the next two decades the company narrowed the gap between itself and its largest competitors by landing a large number of the most sought after accounts in the business. That process culminated on July 12, 2000 when Quad/Graphics signed an agreement to become the lead printer for National Geographic. In the printing industry many considered that account to be “the Holy Grail” in printing. The actual printing of National Geographic did not begin for two years .

The explanations for Quad/Graphics’ growth were the usual suspects. First, there was the quality of Quad’s work, explained, in turn, by Harry’s expectations, the technology used and the quality of the labor force. Second, there was Harry’s special role in customer relations.

Technology was undoubtedly one of Quad/Graphics’ most formidable weapons. In Fennell’s opinion, “ Quad’s ability to develop and build new press technology through its R&D division soon proved to be a key to the company’s growth. Quad attracted new customers because of its research and profited from selling the equipment to others” ” ( Fennell, p108). In 1979 a research and development unit was established by Harry. He named it QuadTech and put his brother Tom in Charge. “ QuadTech’s early successes included two computer-driven machines; a web register guidance system; and an enhanced chiller, a piece of equipment that cooled the warm pages after emerging from the press dryer. QuadTech’s chiller allowed the press to run at speeds never before registered in the industry, a key to efficiency and profits. The Register Guidance System III, which automatically brings the printed image into registration and maintains it during the entire run, would be named Wisconsin’s best invention of the year. Quad eventually sold hundreds of those systems to other printers.”( Fennell, p.109).

Another technology initiative was the creation of a department that developed new and improved inks, the Chemical Research\Technology Department. An important motivating factor here was to bring ink-making in-house. Harry thought Quad/Graphics could learn to do it better than outside suppliers. Similar thinking caused Harry to start his own trucking operation ( Duplainville Transport) and his own pre-press services operation ( Enterprise Graphics, later renamed Quad/Imaging). ( Fennell, p.109).

Harry’s special role in customer relations was that of building lasting ties with customers and telling compelling stories about what Quad/Graphics could do for those customers. As one of those customers put it ( Del Franco,2002):

“ Harry was a good friend of our family and our company,” says David Hochberg, a spokesperson for Rye, NY-based gifts cataloger Lillian Vernon Corp.” He certainly believed in the power of personality in servicing our account and showed he cared by personally getting involved many times. There certainly was a personal relationship with him aside from a business relationship”( Del Franco, 2002).

Home hospitality was an important part of Harry’s customer relations strategy. As Fennell puts it ( pp.238 -239):

“ From Harry’s early days, he saw all of his dealings with clients as a chance to develop mutually beneficial relations. With Betty’s help, they erased the lines between their personal and business lives. Talk to most of Quad’s major clients and they will mention, without being asked, of dining at Harry and Betty’s Pine Lake home, of being invited to Saratoga Springs in August during the race season, of learning about printing at a two-day CAMP/Quad, of weekends in the Dominican Republic. Yes, these were sales and marketing tools Harry used and most of his clients recognized that fact. Yet, the way he and Betty handled these affairs somehow transcended business.”

Or, as David Orlin, senior vice president of operations strategic sourcing for Conde Nast put it ( Fennell, p.245):

“ He and I spent half the night at his home getting to know each other. The uniqueness of Harry was that his business and personal life were very much intertwined, which is very different from executives at any other printing companies. When you are dealing with someone, it is nice to know who they are and where they come from.”

One customer relationship that started off badly had the side-benefit of launching Quad/Graphics into advertising. The case in point was Time magazine’s refusal to give Harry any business in 1981. Harry concluded that part of the problem was Quad’s image in New York. His solution was to launch an image-building advertising campaign. The campaign used humor to get the reader’s attention. Among the headlines used in the ads were “What the Hell is a Quad/Graphics?” and “Pewaukee. What the Hell is a Pewaukee?” The latter ad was accompanied by an out-of-proportion map showing Quad/Graphics’ Pewaukee plant at the center of the world. ( Fennell, p.111).

B. Some critical moments

There were a number of critical moments in Quad/Graphics’ growth history. An early example was Harry’s decision to become one of the industry giants and to borrow heavily to pay for expansion. Here’s Fennell’s summary of that case ( pp.112-114):

“Early in 1983, Harry called together his executive team for one of the most important planning sessions in the company’s short history. Quad had grown into a $45 million business that employed more than 600 people and showed a net income of $3.3 million. The printing industry was consolidating, with small and medium-sized companies like Quad being eaten by larger firms like Quebecor and World Color. Harry told his executives that Quad couldn’t remain at its present size and compete in the future …To pay for this growth, two options existed: borrow money or go public. From his W.A. Krueger experience, Harry learned that being at the mercy of quarterly returns would make him and Quad slaves to the stock market. Although borrowing seemed riskier, Harry knew that in the long run it was actually cheaper because the interest on debt is tax deductible…so the CFO started the hunt for new money…(T)he company engaged in ‘just-in-time’ financing and when money didn’t arrive on time – something that happened more than once- Quad ran out of money for a few weeks. The company could meet payroll with the cash coming in; it just had to slow down what it paid out…On paper it looked frightening…The huge debt eventually fueled rumors in Milwaukee that Quad was a house of cards ready to collapse at any moment “.

Of course, Quad/Graphics didn’t collapse. But Harry was clearly taking risks.

A few years later, Harry experienced another critical situation when a bet he placed failed to work out. In 1986 he bought the John Blair Marketing Company, a publisher of inserts for Sunday newspapers. He renamed the business Quad Marketing Inc and put Paul Moschetti in charge of gaining market share by , in part, using technology to lower the cost of inserts. By 1988 Quad’s market share for inserts was about 35 percent. That was also the percentage of Quad’s business represented by inserts. But the industry was consolidating and one of the remaining competitors, Consolidated Press Holdings decided to gain market share through a price war. That war drove prices below Quad’s costs of production and there was talk about whether or not Quad could avoid bankruptcy. The choices were to find a partner with plenty of cash, sell Quad Marketing Inc., or give the business away.

The situation was dire enough that Harry reportedly thought he was going to lose the company and became a nervous wreck. “ By early July, the banks cut off all funds (and) …Quad was out of money for six weeks, except for checks arriving from customers … No one told Harry about the shattering finances.because of his fragile state” (Fennell,p. 167). Instead, company treasurer John Fowler, Harry’s brother Tom and Harry’s son tried to save the situation. Quad/Graphics was finally bailed out of this life or death situation by Australian media magnate Rupert Murdoch. He drove a hard bargain- Quad had to sell its money-losing insert unit to Murdoch at book value. The deal 10 was accepted, Quad got rid of Quad Marketing and the huge losses it had imposed on the company. ( Fennel, p.170).

VI. CORPORATE CULTURE AND MANAGEMENT STYLE

Because Harry envisioned himself building a unique corporate culture he chose to hire most new employees from the ranks of “ high school graduates from hard-working families with good values – young minds untainted by other workplaces.” ( Fennell, p.173).. As he put it, “ They are the kids in the class who didn’t go to college, who didn’t make it in school for some reason, and in many ways have nowhere to go. And what we do is get them to elevate their sights, to become something more than they ever hoped to be. I like to say we get extraordinary results from ordinary people. Instead of thinking of themselves as printers, we get them to think of themselves as trained technicians who run the computers that run the press…Now, they have jobs that they can be proud of….which is perhaps the most important thing of all.” ( Fennell, p. 173). Later, Quad began targeting community college graduates ( Fennell,p. 179).

“Rather than having all employees specialize, Harry believed that workers who take on various jobs throughout their careers are not only more valuable to the company but also more loyal. ( Fennell, p. 173). Harry developed this approach on his own. But then attended a Harvard University seminar where he read parts of William Ouchi’s Theory Z: How American Business Can Meet the Japanese Challenge. He decided that Quad was already following the Japanese philosophy of a common purpose that employees from top to bottom embrace with fervor. In his February 1982 company newsletter he even bragged about Quad’s independent discovery and practice of those principles ( Fennell, p.175).

One key feature of the Japanese approach was promotion from within and that, too, was a practice that Harry adopted independently. For example, instead of going on a national search for plant managers and hiring someone with years of experience and professional degrees, Harry chose company leaders from within the plant, looking to people he trusted and who were quick studies. That approach made many people loyal. (Fennell, p.182).

Another commonality was the company uniform. That practice was continued after Harry’s death for the reason that it appeared to work. As Harry’s brother Tom, once said, ( “Quadracci Family Has Guts to Zig When Others Zag”):

“ We believe all our employees put our pants on the same way. That’s why the CEO of the company wears the same uniform as the guy on the shipping dock. We don’t want to build any of these walls you see in other companies, where there’s a difference between the suits in the mezzanine and the people on the floor that are actually doing the work.”

Medical clinics were another one of Harry’s employee-centric practices. Once the idea entered his head he approached it with the same “will stop at nothing to make it happen” mentality that characterized his overall approach to business. Harry tried to get his brother Leonard to start the in-plant health clinic. Leonard turned him down but offered to help Harry find someone. Harry advertised the position of physician/medical manager in the Journal of the American Medical Association and through that ad found and hired Dr. Robert Kessler in 1990 ( Fennell, p.201).

Not all of Quad’s innovative employee benefits programs originated with Harry. One that did not, but which he eventually embraced with a passion, was the company’s day care program. The impetus for that came from a former manager of the Lomira (Wisconsin) plant, Gayle Kugler. She was acutely aware of the fact that most child care businesses operated only during normal business hours. That put Quad’s employees in a bind since the company operated twelve hour shifts. Harry had reservations about her proposal for a company solution. But he gave Kugler the go-ahead to research options. When she came up with a viable plan he told her to establish a company child-care center. It opened in 1985 and was called Quad/Care. In 1991 Working Mother put Quad/Graphics on its list of 100 top companies for women and cited Quad’s child care program as one of the reasons ( Fennell, pp. 195-196)

Harry’s interest in and concern for employees in all positions was genuine. And that is the way most employees viewed it. But, when it came to managers, Harry could and did get angry and show it. “ Harry’s singling out of an executive for (such) special treatment happened most frequently from the mid-1980s until the mid-1990s, a huge growth period for the company and an especially stressful time for Harry…The explosions sometimes occurred on Monday mornings after aerobics. Harry required that his executives attend 7 a.m. exercise sessions before their regularly scheduled meeting.Still in their sweaty gym clothes the group assembled in Harry’s office and, over time learned to spot the signals in Harry . Jeanne Kuelthau, Quad’s retired corporate secretary, recalls, ‘ We saw the emotions build. Harry’s temples quivered and we didn’t know who he was going to whip that morning. We all looked around and thought,” Is it your turn today?” ( Fennell, pl.142). Experiencing Harry’s anger was a perk of Quad managers. Employees on the plant floors never saw that side of Harry ( Fennell,p.188).

Harry’s anger could lead to a person being fired on the spot. But, somehow, there was no follow-through and managers learned to quietly ignore a dismissal. Inevitably, Harry would have second thoughts, but instead of apologizing and telling the person they were rehired, he simply acted as if he had never told the person he or she was fired.

Harry’s darker side was something managers learned to accept. In so doing they, themselves, exhibited a rather high level of maturity. Harry’s son Joel put it this way ( Fennell, p.149):

“ Hearing about these experiences from his fellow officers and witnessing his father in action gave Joel Quadracci a helpful perspective. Describing Harry as both a people person and an authority figure, he says his father swung between these seeming opposites depending on the situation. ‘ All of these guys understood that there was a total package there. And ultimately no one left,’ he explains. “If Harry was just about being tough on his leaders, he would have probably lost people. He was tough on them but he was also good to them.”

Effective communication with employees (or partners) was something Harry considered to be one of his strengths. Of course, the employee benefits and practices such as the common uniform were silent signals of what Harry wanted most to say ( We’re a team; we care for one another; we’re partners; management cares for you). So was Harry’s practice of walking the plant floor. Until the company expanded into multiple plants he knew everybody on the plant floor and established personal bonds of friendship with them.

Perhaps the most unusual and indirect method of communication was Harry’s practice of putting on a stage show for all employees. That occurred once a year and consisted of all management personnel putting on a stage show starring themselves. The idea was that the rest of the employees could see managers “making a spectacle of themselves” and thereby showing their common humanity. The first show was a spoof of H.M.S. Pinafore . The idea to do the show was Betty’s and Harry, who was basically a shy person, was hesitant at first. But the experience energized him. He loved the attention, the applause. In addition, according to Fennell ( p.96): “

Something about that evening – being in the limelight, communicating to employees in an entertaining way and seeing them respond –stayed with him and Betty. The experience seemed to feed Harry’s need to be at the center of attention; he sensed he could shape Quad culture in a different way. People could bond, working hard and playing hard in an atmosphere in which they could take risks getting up on stage to sing, even if off-key. That kind of openness and creativity – doing something they may have never imagined themselves doing – might spark new ideas within Quad. ‘

It was really the beginning of our marketing efforts, a very deliberate attempt to place Harry at the center of it,’ said Betty…That show became the catalyst for the rest of the shows, the parties and the mythology that surrounded Harry and Quad.” The first show did not include all employees in the audience. The second show, December 4, 1981, did. That, too, was a spoof of H.M.S. Pinafore. Over the years there were many other shows based on other broadway musicals. But it was the second show that gave Harry a nickname he loved to use…The Admiral ( Fennell, p.103).

VII. THE FIRE, HARRY’S UNTIMELY DEATH AND MANAGEMENT SUCCESSION

“ In 1992, doctors discovered three blocked coronary arteries in Harry’s heart and – in a then new medical procedure – placed stents in them. … Several years after the procedure … his doctors solved his coronary problem, Harry worried about other things. His father developed Parkinson’s and the early stages of Alzheimer’s and as Harry watched him deteriorate, he feared he might be prone to the same fate.” ( Fennell, pp.233-234). And so the matter of successor management became a topic on his mind and on the minds of his management team.

The issue became more pronounced in the following years as the stress of handling a large company periodically pushed Harry into visible moods of depression. Medicine was prescribed and Harry managed the problem. So did the top managers who had an ability to step in and take charge if and when Harry had a bout of depression which temporarily made him ineffective as CEO.

Harry did pave the way for successor management. He originally hoped that his older son, Richard, would follow him. But that didn’t work out and in late 2000 Harry announced to the board that his brother Tom would follow him. That was news to Tom who hadn’t been forewarned. Tom thought that Harry, “ viewed the appointment as a precautionary formality” and didn’t expect to step down anytime soon ( Fennell, p.294).

That was the situation in July, 2002 when a fire broke out at Quad’s Lomira, Wisconsin plant. One man was killed. The company had a disaster plan in place and quickly recovered. In the meantime, a cloud hung over the company while an investigation of the causes of the fire was conducted. It was concluded that the problem was caused by faulty welds, a responsibility of an outside building contractor. Nevertheless, during the investigation and after Harry remained deeply depressed and even indicated a fear that he might go to prison if Quad was found guilty of causing the fire through negligence. As reported by Fennell ( Fennell, p. 319):

“ Tom became concerned when Harry, in one of his agitated moods, told him he thought he was going to jail because of the fire. On another occasion, Harry said he wanted to sell the company. When discussing these issues, Harry asked Tom to go to the customer lounge with him because he feared someone had bugged his office.”

Despite Harry’s worries, the company’s ability to quickly get back to business drew rave reviews from industry observers. That quick recovery from the fire was no accident. It was the result of careful planning. As explained by Tom Quadracci ( Van Meter, 2003):

“Our plant was a gravure plant and due to the high explosive nature of roto gravure we spend a lot of time working on a discovery plan.” 14 Van Meter adds, “ Because of that plan, Quad executives and managers knew what steps to take to get the building back in operation again. In fact, the part of the plant undamaged by the fire was back in operation within 36 hours after the fire was put out.”

Two weeks after the fire Harry accidentally drowned in the lake which his home abutted. He had gone out to take an evening swim on his own, something he occasionally did. Exactly why he drowned, if that is what happened, was never determined. But the autopsy did conclude that a “medical event” that occurred while Harry was in the water might have caused the death. Likely suspects were a heart Arrhythmia or a brain seizure that would have made him unconscious. ( Fennell, p.336).

The fire and Harry’s death bore testimony to the empowering culture that Harry had created, and to the succession planning that had taken place in spite of Harry’s reluctance to let go. Here’s one outsider’s view of that ( Van Meter, 2003):

“ A rogue wave hit Quad/Graphis last July in the form of a catastrophic fire and the sudden and unexpected death of Quad/Graphics president and co-founder Harry V. Quadracci. Quad was able to survive that perfect storm due to extensive contingency planning already in place, said Tom Quadracci, who succeeded his brother as chief executive officer…In 2002, despite the fire and death of Harry Quadracci, Quad/Graphics emerged from its perfect storm relatively unscathed, posting record earnings.”

Among the successor managers ready to take over was Harry’s son Joel who joined the company in 1991 and became president and chief operating officer in January, 2005. Here’s how Joel told the successor management story in a press interview in 2005 (Kearns, 2005):

“ You have to remember when you have an original entrepreneur that comes in and builds a company like this, he’s involved in everything. Micromanaging. He lets the team do their thing, but he’s like the proud parent that wants to keep a hand there. But one of the things that are pretty magical about what he did here is recognize that it’s about the team. At the end of the day he really did operate that way, and had transitioined the team for the next generation.”

“ If you look around this company you’ll see this is a very flat organization. There was Harry, who was chief executive officer and president, and operational vice presidents. So all press room (employees) report to one VP. And that team is what really ran the operations of the company. So when he passed away, he had already basically changed over to the next generation. The average age of our executives is 45, with 20-plus years experience – a very experienced young team.”

VIII. CONCLUSION

One of the finest summaries of the Harry Quadracci story is the following view given by biographer John Fennell ( Fennell, 341-343):

“ When his superiors at W.A.Krueger lost faith in him, he struck out on his own, sketching out plans for Quad at his dining room table. Despite his shyness, he convinced a few investors to become his partners and set out on a course of building a company where management and employees felt like partners instead of enemies, where trust reigned.”

“ Despite skeptics who viewed his debt strategies as dangerous, who thought his efforts to razzle and dazzle constituted hocus-pocus, he turned a $600,000 investment into the third largest printing company in North America…”

“ He did that by tossing out rules, preaching common sense, urging employees to use the same standards in guiding business relationships that they used in their personal lives. He challenged customers, convincing them that in forging a relationship they could both prosper. He won them over with a personal communication style that captivated people.”

“ Harry’s most stunning accomplishment , though, was the culture he built. He infused that culture with his own passion in a way that those who worked for him became passionate, too. “

“ He developed into a master of building relationships, with employees clients, suppliers, financiers – almost everyone who crossed Quad’s path. He was a communicator who used showmanship and symbols to convey his message. He acted boldly and intuitively, investing in plants before he could guarantee customers, seeing opportunities when others didn’t. He used educated hunchmanship, looking at the past, analyzing facts, then spending time listening to clients and wandering around his plants talking to employees before applying that hunchmanship to make decisions …”

“ Harry surrounded himself with exceptional people. He brought out the best in them, making them believe in themselves when they might not otherwise. He showed loyalty to his employees and customers; they returned that loyalty …”

“ As Quad’s success mounted, he plowed profits back into the business and into a rich benefits package for his employees. Then he and Betty supported the communities where Quad plants are located, giving significant gifts to the Milwaukee Repertory Theater, the Milwaukee Art Museum, the Fond du Lac Arts Council,…Saratoga Hospital..the Endometriosis Assocation… a state-of-the-art library in Sussex, …their alma maters..the Waukesha County Technical College Foundation…”

“A man of vast contradictions, he wore them openly. He was wonderfully generous and oddly tight-fisted; decidedly rational and extremely emotional; uncommonly kind and intermittently harsh; exceedingly self-conscious and dazzlingly showy; boldly confident and painfully shy…”

“ Harry paid a price to make his dream come real. He rarely felt a moment’s peace because his creation demanded so much of him. He seemed always driven, but in the early years, Harry was more apt to laugh, to embrace life and Quad’s success with amazed wonder. As the company grew and the stakes got higher, the burden weighed more heavily on him. Yet because he and the company became so intertwined as to be indistinguishable, he couldn’t let go…”

This article was written by Dr. Richard Hattwick.

IX. References

Del Franco, Mark and Paul Miller,”Quadracci Remembered as a ‘True Icon’, KeepMedia, Sept. 1, 2002 , www.keepmedia.com/pubs/CatalogAge/2002/09/01/102686.

Fennell, John. Ready, Fire, Aim. Milwaukee: QuadGraphics: 2006.

Kearns, Patrick, “Next generation of Quad leadership steps up to the plate, Newspapers and Technology, March, 2005,

http://cc/msnscache.com/cache.aspx?q=2712839487060&lang=en-US&mkt=en-US&FO

Van Meter, Mary, “ Dodging disaster: How Quad/Graphics survived the perfect storm,” Newspaper and Technology, www.newsandtech.com/issues/2003/nt/06-03_quad.htm.

Whitaker, Mark, “The Editor’s Desk,” www.keepmedia.com/pubs/Newsweek/2002/08/12/311395

ANBHF Laureates

Our laureates and fellows exemplify the American tradition of business leadership. The ANBHF has published the biographies of our laureates and fellows.

Some are currently available online and more are added each month.