Barber Greene

Introduction

Barber Greene

Barber Greene

October 30, 2014

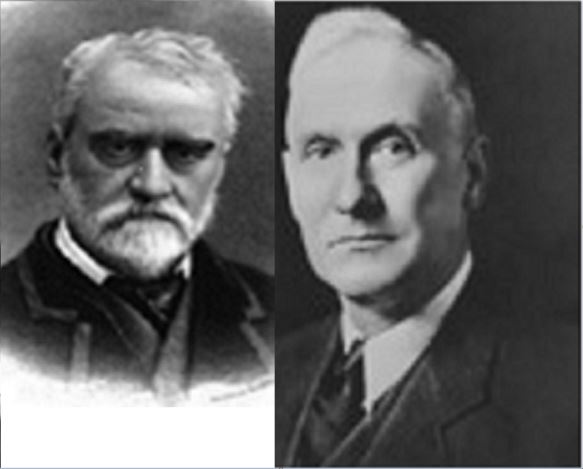

WILLIAM B. GREEN & HARRY H. BARBER

BARBER-GREENE COMPANY

WILLIAM B. GREENE

and

HARRY H. BARBERBARBER-GREENE COMPANY

(1916-1976)

by Dr. Richard E. HattwickProfessor of Economics (Retired)

Western Illinois University

INTRODUCTION

This monograph briefly sketches the entrepreneurial history of one of the nation’s major corporations.This

particular history dramatically illustrates the role of technology in creating a better life for mankind and the

role of the “free enterprise system” in encouraging men like Harry Barber and Bill Greene to dedicate their

lives to the task of creating that technology.

BARBER – GREENE

The Barber-Greene story is an outstanding example of the interplay between the profit motive and broader

social objectives within the American business organization. The company was founded in 1916 by two

mechanical engineers, Harry H. Barber and William B. Greene. Barber and Greene were motivated in part by

the potential profits to be earned. But the co-founders were also motivated by the vision of a broader

business purpose. As Greene put it several decades later:

Our role has been in easing the physical burdens of mankind. Our machines dig the ditches, shovel the coal,

build the roads and do those dirty, rough heavy jobs formerly assigned to our newest immigrants – the men

with the shovels and the wheelbarrows. We have often had the satisfaction of seeing a laborer transferred

from a ditch to the controls of a machine, thereby acquiring a new dignity and a new outlook for himself and

for his children. (Greene, 1966, p.4).

The Barber-Greene story is also a fascinating chronicle of growth and change in the modern corporation. The

company started out as a small business and enjoyed modest growth until the Great Depression forced the

organization to fight for survival. World War II caused the company to experience rapid growth and by the

end of the war, Barber-Greene had become a very large business, known world-wide. In the post war era

numerous organizational changes were made to enable the company to cope with its new size and with the

new economic environment. The changes culminated in the adoption of a comprehensive and detailed

system of planning and control in the late nineteen sixties and early nineteen seventies.

THE FOUNDERS’ BACKGROUNDS

An important part of the Barber-Greene story is the background of the founders. Both men represent

backgrounds common to mid-western American businessmen of the era. And the events that caused these

men to “strike out on their own” are also typical of that period of American business history. Here, in the

words of Greene himself, are the important facts regarding the founders’ backgrounds:

Harry H. Barber was born in Freeport, Illinois, on January 18, 1878. I (Greene) was born in Lisle, DuPage

County, Illinois, on September 4, 1886.

We were both born and raised on farms, of pioneer stock, of good parents, in a wholesome environment;

and we each graduated from the University of Illinois as Mechanical Engineers. (Barber 1907, Greene 1908).

Our common experience of farm life during the turn of the century gave us similar points of view and

attitudes. We each shared in the farm work as our school work permitted, and we experienced long hours of

hard work but not so hard as to preclude our realizing the satisfactions of farm life and participating in the

constant planning for increased farm productivity which we could observe resulting in increased leisure and

more amenities and comforts.

Harry Barber’s college years were postponed by a stint in the Freeport freight depot of the Illinois Central

Railroad after high school. He was eight years older than I and well matured when he entered college. Harry

had summer employment with Link-Belt Company which oriented him to the materials handling field; but on

graduation, he joined a newer company in that field, the Stephens-Adamson Manufacturing Company of

Aurora, Illinois, together with a classmate, Earl Stearns, who became an important addition to our

organization years later.

In the fall of 1907, a severe financial panic struck, and we of the Class of 1908 who followed found little

demand for our services. I got a job that fall with the original Robins who had pioneered belt conveyors

(now Hewitt-Robins Co.) And thus also was introduced to the materials handling field. After two years “on

the drawing board,” I transferred to Stephens-Adamson.

…Harry’s greatest talent was his unusual originality and ingenuity. He acquired in the field a good sense of

economic need, and in the shop a sense of structure that went beyond stress diagrams and tables of

strength of materials. His conclusions seemed more intuitive than results of slide rule and formula

calculations. This was coupled with a contagious enthusiasm and an unfaltering drive.

I had become deeply interested in the social implications of machinery that could do the work of men. In

consequence, I found myself more interested in broad applications than in nuts and bolts, and thus in

promoting these fruits of our engineering. This led to my becoming Advertising Manager and in that capacity

creating and editing a house organ which I christened THE LABOR SAVER. This was an appropriate name

which was retained by Stephens-Adamson until the years of the depression when the idea of “labor saving”

stood accused (Ibid., pp. 4-5).

FOUNDING THE COMPANY

As fellow employees at Stephens-Adamson, Harry Barber and William Greene developed a friendship and out

of that friendship emerged the courage to set up their own business. Greene describes these developments

as follows (Ibid., pp.4-10):

Out of our continued interest in saving labor, we became aware of fields not served by Stephens-Adamson,

and which they did not feel were compatible with their heavier line. Also we had been observing the large

number of small isolated jobs where the material was handled by shovel and wheelbarrow, and which might

be helped by portable conveyors. In retail coal yards, they had to unload cars by hand, and to load wagons

by hand from the sheds and piles. Contractors, gravel pits and small industries all had to move material the

hard way.

Henry Ford had dramatized the possibilities of mass production. He had given new impetus to the process of

mechanization and repetitive manufacture, and his spectacular example created a favorable public

understanding of the social benefits of mechanization, standardization, and the resulting increased

production per man. Also “Mecanno” toy building sets had become popular, in which standard pieces of

components could be assembled into a multitude of combinations.

While automotive quantities could never be achieved in a line of conveyors, repetitive manufacture was a

possibility. Standardized components including terminals and intermediate sections could be developed and

carried in stock, thus allowing a wide range of customer choice, off-the-shelf, from a relatively small stock.

(This permitted production in quantity, thereby lowering unit costs and customer prices.)

As these ideas evolved, we became obsessed with the idea of our own business. Neither of us had the

capital nor the desire to undertake a venture alone. We felt that the other’s abilities were necessary

supplements to our own and that a balance of combined talents would yield more than the sum of our two

separate abilities.

Our list of potential products in the field of Standardized, Continuous Flow, Materials Handling Machines were

impressive–possibly 20 items. None were designed but that was not critical. What was important was

gauging the untapped market–the small isolated jobs that could be economically mechanized out of the

shovel and wheelbarrow stage. That could hardly be tested without real venture.

To provide manufacturing facilities, I interviewed W.S. Frazier and Company of Aurora (in what is now the

Vendo plant) whose horse-drawn carriages were becoming obsolete and whose racing sulkies, while not

obsolete, could not take up their slack. Yes, they had available shop space and they would be glad to

undertake our manufacture for us as sub-contractors, we to design and sell and assume the risk. It was

premature to work out detailed business plans, but our mutual interest was sufficient assurance that we

could work together.

So we decided on our initial step. Harry was to quit his job, complete his designs, get some working models

and test out our market. I would keep my job so we could have one salary coming in until things were ripe

for more active promotion. That was a nice conservative plan.

We arranged an evening to broach our plans to the “old man”–Wiley W. Stephens, the very much liked and

respected president of Stephens-Adamson, who had hired each of us. It came as a shock to him to think of

losing two of his hand picked trainees, and it was complicated by real mutual affection. We all agreed to take

time to study it in further detail and let him review it with Dave Piersen, then Vice-President and General

Manager and slated to succeed as President. Dave was a realist. We had already “tasted blood” and there

was little likelihood of our continuing to be satisfied under their jurisdiction. Further, Dave thought little of

the idea of my staying with S-A until our own plans had matured further; saying that “your heart will be in

your own business and you won’t be worth a damn to us.” And thus a company was born.

After winding up details of our respective jobs, we left in good will with advice and with the best wishes of

the officials and of our many good friends.

Our basic policies had already been hammered out; we would design and sell Standardized Materials

Handling machines. As equal partners, we would observe with each other an equality of ownership,

compensation and authority; Barber to carry the responsibility of design and manufacture; I, the sales,

finance, and business administration.

We would consult and agree on all matters of major importance in each area of operations.

It was taken for granted that we would be ethical in all aspects of our business, scrupulous in honoring our

obligations, with all our operations consistent with the public welfare. We would be model employers,

concerned for our employees’ growth and development, and for their welfare; as generous in our

remuneration as our competition would permit.

For our operating plans; we had agreed on the name Barber-Greene Company. We would subcontract our

manufacture to W.S. Frazier and Company. We had each committed ourselves to an investment of $3,500 to

be advanced as needed. Our wives had budgeted our personal expenses (salaries) at $150 per month. We

would use the Barbers’ guest room as our office, temporarily; also Barber’s antique portable typewriter which

I mastered sufficiently for our first letters.

For immediate operations, we would: …build a portable belt conveyor as quickly as possible and get it

installed in some coal yard as a demonstration unit, and then test the market with advertising and sales

calls.

In this initial planning, our wives participated and concurred. They were critically important and if either one

had lacked the vision and the confidence and the fortitude required at the beginning, as well as during the

good and bad years that followed, I would not be writing this history. They had proposed the reduced

salaries that we paid ourselves. They managed their households within the budgets, even allowing for our

Model T’s and for breaks in the routine for fun and relaxation. Their confidence in us and in our venture

provided a sustaining influence often needed.

Now the challenge of converting dreams into reality and of piloting a new business through the rough

waters. Our beginnings were modest but fast moving. On our official birthday, Saturday, October 21, 1916,

we opened a bank account with the first installment ($1,000) of our initial investment. And over the

weekend, we were busy with detail plans.

The following Monday, we took the train to Chicago, interviewed possible suppliers, and established our

credit with General Electric and one or two others. We ordered an electric motor, two wood pulleys, 32’6" of

18" 4-ply canvas belting, and sufficient steel for a conveyor. I think there were some other things, including

two wrenches and a machinist’s hammer, which we carried out with us.

The balance of the week was spent in fabricating and assembling Conveyor No. 1 in the Frazier shops. While

Harry was supervising the manufacture, I was busy getting some of the paraphernalia for a simple business,

designing and buying forms and more important, getting our first order. The order came from our nearest

neighbor, the Lilley Coal Company.

Having made their first sale, Barber and Greene began advertising their product in the Retail Coalman.

Orders began to come in for Barber-Greene conveyors and the company was on its way. As the conveyor

business expanded, Barber-Greene received through Stephens-Adamson an inquiry from a cement company

regarding the possibility of developing a self-propelled self-feeding bucket loader for handling cement

clinkers. Barber worked on the concept in his basement and in a matter of days came up with a full size test

unit. The product was successful and by the end of 1916, Barber-Greene was selling two product “lines” to

the public.

INITIAL SUCCESSES: 1916-1930

The first decade of Barber-Greene’s history was a period of growth and technical accomplishment. Once

again W.B. Greene captures the essence of the period. In his words (Ibid., pp.12-13):

At the start of the decade, orders for conveyors were rolling in beyond our capacity. Agents and dealers kept

applying for territories, and although these had to be judged with little or no personal contact, results were

surprisingly good. Mussens Ltd. of Montreal, our first dealer appointment, has continued to represent us

through the years as one of our leading representatives. Brandeis of Louisville and Zeigler (now Zeco) of

Minnesota also date back to those early years.

In spite of the activity and profit in our initial conveyors, Barber was not satisfied. While these first conveyors

reduced the cost of unloading cars, they did not fully mechanize the job, and dealer salesmen lacked the

patience and ingenuity to adapt them to existing sheds. Barber’s answer, in 1917, was a conveyor on an

elevating rack (Style E) adapted to stockpiling and to unloading from dump cars. This soon became, and

remains, the accepted standard.

We soon took over our own assembly in a small unheated warehouse which we leased from Frazier for $300

per month and thus we became manufacturers. Frazier continued to fabricate for us.

In the meantime, we were studying expansion plans, checking buildings and sites both in Aurora and

elsewhere. The actual steps taken were:

Incorporation for $50,000—(500 $100 par shares)

Exchange of our partnership fro 250 shares

Sales of balance of stock at par: 25 each to ourselves; 60 to McIllwraith; 140 to selected individuals “who

could afford a risk and who would not interfere with our management.”

Purchasing of the first two lots of our present site.

Contracting with W.H. Graham and G.A. Anderson on a 10-year purchase agreement for construction of

Building No. 1 (70' x 100') and a 20' x 40' adjoining office.

We moved into the shop late in December, 1917. That was the winter of the deadly influenza, of the big

snow, and of the coal strike and heatless Mondays….

In 1918, confident of a peacetime market, after the Armistice, we authorized an increase of our capital to

$250,000, and strengthened our Board of Directors by two additions. One was H.S. Capron, a Champaign

banker, a brother-in-law of Barber’s, who thereafter served as our financial advisor. He proved to be helpful

in establishing bank credits which might not otherwise have been available to us. The other was my brother

H.S. Greene who was to become Vice-President and an energetic and competent sales manager from 1921

to 1929.

In 1922, our retail coal business had become quite competitive. It was attractive to us, however, because it

was closely related to consumer needs with little drop-off in a depression. We developed a very complete

line of belt and flight conveyors together with wheel and crawler-mounted flight loaders with screens and

power hoists. This was a close margin bread-and-butter business, active until natural gas superseded coal

for house heating after World War II.

The first experimental ditcher, in 1922, was mounted on a bucket loader chassis. However, the feeds and

speeds and bearing pressures called for a special Chassis for later models. The first production model was

released in 1923 and it found a ready market that had not been anticipated by manufacturers of the large

trenchers. We found that we could dig in coral rock so we were ready for the spectacular Florida land boom

in 1926. Surprisingly, neither sales nor production set our limits in Florida, but rather a shortage of railroad

cars.

In 1919, we had an opportunity to try out a loader on concrete road construction. The practice had been to

accumulate windrows of aggregate on the roadway and from these to supply (by wheelbarrow) the mixer.

Our loader replaced the men shoveling to the wheelbarrows. Later, separate stockpiles of sand and

aggregate were accumulated at the source of supply, and loaded by loaders equipped with measuring

hoppers onto light trucks hauling to the mixer on the roadway. A typical setup included two long conveyors

(one to build each pile) and two loaders (for the sand and the gravel). This became standard procedure

throughout the twenties, almost a monopoly for us. (This paragraph was added to the text by W.B. Greene

in 1976.)

By 1926 loaders and conveyors were just beginning to feel the competition of cranes and bins in concrete

road construction. Coal business was still good and ditcher sales were increasing. Events conspired to give us

a sales volume not equaled again until 1940, earnings not equaled until 1941, and a profit percentage not

since equaled.

From 1927 through 1930, Barber-Greene continued its profitable existence, but sales dipped, due in part to

increased competition. The competition was felt most keenly by Barber-Greene’s conveyor and loader line.

More than a dozen competitive methods were making major inroads on that end of the Barber-Greene

business. Barber-Greene partially offset the sales decline through expanded sales of ditchers and through

greater concentration on the industrial market. To “get concentration on this market”, branch sales offices

were set up and the aggressive sales force directed by H.S. Greene attempted to increase Barber-Greene’s

penetration of the industrial markets.

Out of the increased sales effort there arose a classic organizational problem. The sales force developed an

interest in having new products to sell and H.S. Greene began to attempt to “sell” Harry Barber on product

concepts suggested by the field force. The result as summarized by W.B. Greene was that, “The Sales

Department … exerted pressures for changes and developments without full appreciation of the design

problems and this led to an impasse. This conflict in philosophy was only resolved by H.S. Greene’s

withdrawal from the Company in early 1929 (Green, 1966).

H.S. Greene’s departure stands out as the single example of a major conflict among the top management

group at Barber-Greene. Such a small amount of conflict is surprising and the explanation for the amazing

degree of harmony during Barber-Greene’s first forty years is to be found in the personality of W.B. Greene.

“Bill” Greene was a born peace-maker – a man who practiced the precepts of “organizational development”

long before that personnel management concept was developed. In order to fully appreciate the importance

of Greene, it is helpful to compare his leadership style with that of Harry Barber.

Harry Barber demanded much of his employees, yet earned their respect through his own technical

brilliance, drive and enthusiasm. Old timers still recall the apprehension with which a department would be

filled when it became known that Harry Barber was coming to “check up” on that department. Such

occasions could result in hard feelings for a time, but they also “kept the organization on its toes.” Barber’s

style was common among business leaders in those days and it produced results.

But Barber-Greene was unusual because of the presence of Harry Barber’s partner. Bill Greene provided the

personal touch that Harry Barber lacked. When employees had problems of a sensitive nature, they would go

to Bill Greene and receive a warm and understanding audience. Greene, too, set high standards, but he

enforced them with a courteous touch that will probably never go out of style. Once, for example, Greene

happened upon a group of employees who had extended a noon-time Christmas dancing party into the

afternoon working hours. Greene deftly and pointedly led one of the women onto the dance floor, completed

the dance and without saying a word left for his office. Everyone else went back to work. On another

occasion Greene’s assistant, Jack Turner, was upset by an error he made. Bill Greene sat down and

proceeded to tell Turner the story of the time when Bill Greene had made a similar but even more costly

mistake at Stephens-Adamson. Turner went home that night with heightened loyalty to the organization and

a renewed determination to give the company his best efforts.

Bill Greene’s personal touch was complimented by his deep respect for Harry Barber. Bill Greene believed

that it was Barber’s inventive genius that brought forth the company’s stream of new products. Greene saw

his most important role as that of supporting Barber’s genius and seeing that everyone else was motivated

to give their full support. Bill Greene was determined to build an organization held together by love and

mutual respect within the management group. He was successful.

In 1929 a development occurred which was to have a profound effect upon Barber-Greene. In Green’s words

(Ibid., p20, 1976):

Our most difficult, as well as most successful development started in the fall of 1929. Messrs. George Craig

and Hugh Skidmore of Chicago (Asphalt) Testing Laboratory, called to interest us in an application for our

loader for upgrading existing gravel roads into low cost asphalt roads. Their particular application didn’t pan

out but they did introduce us to the asphalt paving field and we used them thereafter as consultants on our

various developments.

This occurred just when we were desperate to fill the gap caused by cranes and bins replacing our conveyors

and loaders in concrete construction.

Our loader became the key unit in the resulting travel plant. At first the loader carried a small mixer but the

need soon led to a separate trailer unit carrying the mixer and the continuous metering devices for the

aggregate and bitumen. Low cost asphalt road construction had been partly mechanized by a rather crude

method of blade mixing (with road graders) on the highway subgrade. Our method superseded that, offering

more accurate proportioning and mixing and less vulnerability to weather.

During the depression years, we were able to sell about two travel plants a year to venturesome contractors

on a rental-with-option-to-purchase basis. Acceptance was slow but none were rejected and thus we

gathered valuable experience in the low cost paving field while making the development pay its own way.

Ash (Barber) cut his eye teeth on some of these service jobs as he joined the company after his graduation

in 1933.

SURVIVAL DURING THE DEPRESSION:

1931-1936

The Great Depression of the nineteen-thirties was a period of severe hardship for Barber-Greene. As W.B.

Greene, recalls (Ibid., pp.20-21):

The depression was an economic and social catastrophe. While it started with the spectacular crash of the

stock market on October 29, 1929, followed by minor reverses and succeeding major breaks, the full impact

of the crisis came two years later.

There were frequent assurances of ‘recovery just around the corner,’ and appeals not to ‘rock the boat’ and

‘business as usual.’ We made a fair profit in 1929 and were still slightly in the black in 1930. Our new

asphalt road machines were promising and it was logical to assume that vitally needed road construction

would be continued as an economic stimulant.

For production of our new asphalt machines we borrowed $165,000 early in 1931 on a bond issue, and we

set the foundation piers for an extension to Building No. 3. A few months later the economy slumped further

and the future became so unpredictable that we canceled the building program. The piers remained as

monuments to our frustrated hopes until 1943.

Contrary to some in our industry … we did not reduce wages and salaries until April 1931; and, during the

previous winter, we created employment by production schedules in accordance with our seasonal practice.

A schedule of 30 ditchers was produced in the winter of 1930-1931, but ironically, ditchers became a symbol

of the machines that took jobs away from men. Some were bombed on job sites. Most of that last schedule

stayed in our inventory for many years.

Retail coal … proved to be our most stable market … Later as the Government undertook public works, we

were able to sell permanent and special conveyors for some of the large dam jobs … The availability of both

engineering and shop capacity made this a fertile period for special jobs and these enhanced our engineering

reputation…

Business reached a low in 1933 after almost over-whelming losses. We were finally forced to subordinate

everything to the one goal of Company survival. Individual employee problems were beyond our ability to

consider. Each family had to adjust to reduced incomes and some laid off had to resort to Federal make work programs.

Every transaction had to be considered in terms of ‘cash gain’ or ‘cash loss.’ A sale of surplus inventory

might show a loss but still yield invaluable cash … Depreciation was a non-cash cost. Part of normal

maintenance could be deferred…

We finally reached a point with key salaried personnel where, instead of further layoffs, we allocated each a

percentage of billed shipments, resulting in very slim pay checks without reduced hours. This was painful but

not protested…

We never missed meeting a payroll; we never skipped an interest payment and we paid all our creditors in

full.

… After struggling through another loss year, dawn broke in 1936 … Profits that year were $82,000 which

made us again eligible for bank credit and once more we were on own way.

Despite the hardships of the middle 1930’s, Barber and Greene never lost sight of their need to continue new

product research and development. As explained by Greene (Ibid., p.21):

While development expense was greatly reduced, we never considered its elimination, that was our ‘seed

corn’ – the source of future earnings.

RECOVERY AND EXPLOSIVE GROWTH:

1936-1945

Barber-Greene’s recovery after 1936 was suddenly accelerated by the outbreak of World War II. The war

created a huge demand for machines that could be used to build roads and airports. Barber-Greene had

spent the Depression years holding onto and improving its technological capability in these areas and the

company became a major contributor to the successful defense effort. In 1936 Barber-Greene shipped $1.5

million worth of equipment. By 1943, the peak war year, Barber-Greene’s shipments totaled over $11

million, of which $9 million went directly to the military. During the course of the war, “There were miles of

runways rapidly constructed in this country; scores of airports built or resurfaced in England … many airports

quickly laid in North Africa just prior to the invasion of Sicily … an elaborate chain of airports built through

the Aleutian Islands; … (and) many ‘B’s Nests’ which spotted the Pacific for … B-29’s (Turner, 1966, pp.28-

29).During this period Barber-Greene became a “big business.” The number of employees rose from 265 in

1936 to 1024 by 1943; a Personnel Department was established; and a world-wide demand for BarberGreene’s paving technology emerged.

As World War II drew to a close, a new Barber entered the ranks of top management. Harry Barber’s son,

H.A. “Ash” Barber obtained a B.S. degree in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Illinois and joined

Barber-Greene in 1933. By the late 1930’s, Harry Barber had begun to suffer from high blood pressure. Ash

Barber began to assume many of his father’s former responsibilities and a new team of Greene and Barber

began to emerge.

THE GOLDEN YEARS OF GROWTH:

1946-1966

At the end of World War II, Barber-Greene entered a twenty year period of rapid and profitable growth. The

growth and the profits were based on four factors: (1) a well organized sales effort managed by W.B.

Greene, (2) the company’s decision to set up foreign “joint partnerships”, (3) the innovative product line that

Harry Barber had originated and which the engineering department under the direction of Harry’s son, “Ash”,

continued to develop, and (4) the post war boom in U.S. highway construction.

The sales effort grew out of discussions between Harry Barber, W.B. Greene, and “Ash” Barber. Out of

those discussions emerged the conviction that a unique post-war opportunity wold emerge in the form of

large new sales opportunities (This seems obvious in retrospect, but at the time, there was a great deal of

uncertainty as to whether or not the post war demand would materialize). In order to capitalize on the

anticipated opportunity, Barber-Greene decided to establish a sales organization based on a separation of

sales into a Construction Division and an Industrial Division. It was further decided to switch the primary

emphasis from selling through Barber-Greene sales offices to selling through independent distributors.

The foreign expansion fulfilled a long standing goal of W.B. Greene. In the nineteen twenties he had become

active in an association of export companies that was formed to promote exports. As World War II drew

towards its close Bill Greene traveled to England to investigate the possibilities of setting up an operation

there. The result was the establishment in 1946 of a joint partnership with Barber-Greene’s British dealer,

Jack Olding and Co., Ltd. The partnership, “… combined the name, products, techniques and capital of

Barber-Greene Aurora – with the management talents, national understanding, (and) marketing knowledge

… of Jack Olding.” (Barber, 1966, pp.36-37). The new company sub-contracted manufacturing to British

manufacturers. In the following years similar arrangements were made in Australia, Brazil, Mexico and the

Netherlands. The foreign expansion was also promoted by the establishment of a world-wide marketing

operation headquarters in Aurora.

Developments at the engineering end of the business were also crucial in this period. As explained by “Ash”

Barber (Ibid):

Barber-Greene is an engineering company and its life blood is the flow of engineered products and

applications … The basic inventions and developments of Barber-Greene during its first three decades

became widely recognized and accepted during World War II. Much of this earlier development was created

and executed by a relatively few talented individuals … The detail design at the beginning of the decade was

based on pre-war standards. Considerable modernization was immediately necessary … This tempo could

not be sustained by the older and experienced engineering talent, so it was necessary to follow the same

course as in marketing and production. The projects were split off and then subdivided again under the new

and less experienced engineering personnel who substituted enthusiasm and energy for experience and

caution.

Management changes were several in nature. At the top of the organization there was a peaceful

transference of the presidency from W.B. Greene to “Ash” Barber in 1954. W.B. Greene remained Chairman

of the Board. Also included on the new top management team were: Sam Faircloth, Vice-President and

Production Coordinator; E.H. Holt, Vice-President and Director of Sales; Jack Turner, Vice-President and

Director of Publicity and Promotion; H.E. Herting, Vice-President and Comptroller; R.C. Heacock, VicePresident and Director of Manufacturing and Engineering; J.M. Spence, Treasurer; W.A. “Alex” Greene,

Secretary; Urban Hipp, Assistant Treasurer, and F.J. Merrill, Assistant Secretary.

In 1948 in the middle of the organization there was created an unusual entity – the Junior Advisory Board.

This was a formal organization of younger middle management persons. The board met regularly to develop

and recommend new corporate projects, such as personnel policies and order entry systems. The Junior

Advisory Board was adopted primarily because of its management development potential. As Ash Barber

once put it.

The Junior Advisory Board … contributed greatly to individual and group growth – particularly to interdepartmental coordination and understanding. This is not the best method for ‘running a tight ship’, but it

did provide the strength for the growth from within multiple decision making areas.

There was also a change in ownership. By the mid-1950’s Barber-Greene had grown to a size necessitating a

major decision. As Ash Barber put it (Barber, 1966, pp.44-45):

Barber-Greene had been a relatively “closely held” company. To continue to do so would probably mean that

the Company’s growth and direction would have to be curtailed. This would mean a reduction of opportunity

for many vital people in Barber-Greene. This course was not acceptable.

Thus there were two alternatives open – merge with a compatible and financially strong company – or

declare and pursue a corporate course as an independent company with a “publicly owned” broadened base.

This was thoroughly discussed between directors and officers, co-founder and sons, and key management

people. The decision was unanimous. Barber-Greene was bigger than any one of us, or our families.

Thus it was that in 1958 and 1959 there took place a series of events that led to a successful public stock

offering and the listing of the shares in the “over-the-counter-market.”

One benefit provided by Barber-Greene’s decision to go public was the ability to merge with Smith

Engineering Works of Milwaukee in 1960. Founded by Thomas L. Smith, the firm was directed by Charles F.

Smith during its crucial period of growth in the period 1913-1951. Barber-Greene had a policy of avoiding

mergers merely for the sake of sales growth, but the Smith merger was attractive because Smith produced a

line of aggregate processing equipment that nicely complemented Barber-Greene’s product line. In addition

there was a long association between the companies. Smith bought Barber-Greene conveyors to use with

their crushers, and the two companies had jointly bid, manufactured and erected jobs for years. Thus,

Barber-Greene’s decision to go public was the last step needed to permit a merger.

“ASH” BARBER’S TIME OF TRIAL:

1966-1973

By the mid-nineteen sixties, Barber-Greene’s business environment began to change significantly and in 1966

“Ash” Barber found himself at the head of an organization that was in trouble. The two major changes that

occurred in the environment were: (1) the emergence of strong competitors, and (2) a sharp slowdown in

the industry-wide demand for most of Barber-Greene’s product lines. When these changes occurred, BarberGreene was organized “loosely” in terms of internal controls and management information. This loose

organization had been entirely satisfactory for the period of rapid growth when the emphasis was upon

seizing opportunities. But in the new era of limited opportunities, tighter controls were needed. In addition,

Barber-Greene was organized along functional lines with decision-making concentrated in the hands of the

president. This structure had been workable when the company was smaller, but by the mid-1960’s there

was clearly a need to decentralize decision-making. For the better part of the decade that followed, “Ash”

Barber devoted his energies to the task of leading Barber-Greene through a reorganization which

decentralized decision-making, installed the controls and introduced strategic planning. The result was a

turnaround that began showing up in improved levels of profitability by 1972.

The need to decentralize decision-making was recognized as early as the late nineteen-forties. However, Bill

Greene and Ash Barber moved slowly and methodically in tackling the problem. The goal was to provide the

younger persons in the organization with decision-making experiences that would prepare them for top

management roles in the future.

Ash Barber spent more than five years in the early nineteen-sixties studying organizational alternatives,

analyzing the professional growth and development of the younger management talent that would have to

implement the new system, and analyzing the management information needs that would be generated by

the new organizational approach. In 1966 Barber felt that conditions were favorable for action, and, as the

first step in bringing about the needed changes, he brought in an outside consulting firm to evaluate the

situation and recommend changes.

In 1967 the consulting firm made a number of recommendations, including the suggestion that BarberGreene be reorganized along product group lines with each group as a profit center. Barber had expected

such a recommendation and within a matter of months, management had established five product groups.

The five groups were: construction equipment, industrial applications, material handling, repair parts and

Telsmith (formerly Smith Engineering Works).

The consultant also recommended the adoption of a formalized planning process and the creation of a

management information system to support the planning. These recommendations were also expected, but

their implementation required several years of development. In 1967, Ash Barber initiated this long process,

and entered into the most trying period of his business career. It was a difficult period for Barber-Greene

because the changes could not be made quickly. The data base for effective planning by product line had to

be created before effective decisions could be made and the entire organization hd to learn how to operate

in a formalized planning environment. Ash Barber expressed the early frustrations when he said in one of his

memos to the Chief Executive Group (Barber memo, Feb. 1968):

We have been under way with our first experience in the new responsibility budget procedure. It has been

frustrating because of the unraveling of the duplications, oversights, miscoding, etc. It has been particularly

frustrating because of the lack of comparative history and the presently unfinished “cost transfer”

information…

Nevertheless, it is my impression that we have come a long way… However, it is also apparent that fiscal

1968 will be a major setback to our financial progress. …

If we were clearer in our individual product line profitability, and clearer on our forward planning profitability

projections by product line and program, then I would advocate an immediate realignment of resources no

matter where the restructuring fell. We are fighting desperately for this information and when it emerges

and when we crystallize our strategy from it, then realignment will take place. This company is going to

become a profitable growing company for everyone’s sake.

By the Fall of 1968, the budgeting and forecasting process was sufficiently well along that Ash Barber was

ready for the next step. As he told a group of district managers on October 14, 1968 (Budgets and

Forecasts, Oct. 1968):

We are formalizing our Corporate Planning. That means that we will emerge with a corporate plan – not just

a plan in words and objectives – but a plan that has been converted from assumptions and decisions into

finite figures that are summarized into a profit projection … (and) that will be used to measure the success in

executing that plan after the fact are in …

The plan will cover a fiscal year span and another form of plan will cover the next five fiscal years. The next

fiscal year plan will be reviewed and updated halfway through that year. The five-year plan will be reviewed

and updated once a year for the new five-year span ahead….

This is the program ahead of us. The concepts are not new to industry. Corporate planning has become well

established in the last decade. The General Motors, DuPonts, General Electrics, etc. have been leading out

on these concepts because it became a business necessity. Much of the recent success in some of the larger

industries is credited as a direct result of these planning and control concepts. There are other large

industries that have slipped back in the last decade and much of their failure has been debited to their

unwillingness or inability to tackle formalized planning and control.

Let me be clear on one very important point here. A business fundamentally will rise or fall depending upon

the combination of its ingenuity or inventiveness; its attitudes, talents, and judgements, its over-all

comparative productivity, and its related raw materials, customer acceptance, economic climate, etc. No

Corporate planning or control concepts will substitute for these fundamentals. However, when two

businesses each have the same potential for these fundamentals, the business that learns how to establish

plans and control to those plans under complex inter-relationships will emerge ahead. In this competitive

business world, we intend to be one of those businesses that is emerging ahead.

But this is not simple, and it is not the kind of a program that ‘doers’ enjoy. It’s hard grinding work to put

down finite assumptions and decisions on paper. It’s frustrating to be forced to select one opportunity when

we would like to take advantage of two. It’s not pleasant to control where expansion at the most familiar

center seems so easy; or to force talent, resources, and achievement into a strange channel that does not

come easy….

We at Barber-Greene decided over three years ago that if we were going to compete as a multi-operation

with multi-decision making centers, then we had better be able to provide a formalized planning and control

program that would assist in the optimizing of Barber-Greene’s total direction, growth and success. We fully

realized that we were faced with the development of a management system equally, if not more complicated

than the one at General Motors or at Caterpillar…

During the next few years Ash Barber devoted his total efforts to the task of implementing the new system.

The frustrations continued, and the financial rewards were slow in coming. Earnings per share declined

steadily from a high of $1.99 in 1966 to a low of $0.67 in 1969. They rose to $1.09 in 1970 but then fell

again to $0.85 in 1971. But by 1972 the financial picture brightened considerably; earnings rising to $1.15.

By 1975 earnings had risen to $3.40 per share and the turnaround had been completed (August 30, 1975,

Officers).

In the process of implementing the new planning and control system, Ash Barber adopted many established

procedures that had been proven successful by other firms. But, being the innovator that he was, Barber

could not resist trying to develop some new concepts and techniques unique to Barber-Greene. Some of

these attempts failed. Others were outstanding successes. One such example was the accounting system. As

Barber put it (Ibid):

The accounting systems – particularly cost accounting-systems – of companies that are growing are

periodically in need of updating; ours was no exception. We decided that instead of just updating, we would

design an entirely new system that would give us the kind of information flow we needed for a formalized

program for planning and control of the future. We were pleased to hear the other day from one of our

experienced outside auditors that, in his judgement, our new accounting system was ten years ahead of

corporate practices.

Probably the most innovative development during this period was the implementation of the production and

inventory control system and, in the years following, the cost accounting system resulting from the same

data base developed for inventory management. This system stood out for two primary reasons.

First, through thousands of hours of personal effort in the form of writing, teaching and discussing concepts,

Ash Barber set out to develop the system by concentrating on what was theoretically correct rather than

analyzing what was done and modifying or improving the existing method. The concepts of time of order,

quantity or order and cushion (safety stock) techniques went well beyond any published literature available

at that time.

Second, the implementation of the system resulted in focusing the attention of the total organization on the

future under a disciplined formal planning process. Perhaps more than any other factor the planning system

solved the frustration found in many complicated manufacturing businesses where top management decides

on a product or marketing direction but the manufacturing system, based upon historical data, is incapable

of responding to significant changes of direction.

In 1971, with the “turn-around” underway, “Ash” Barber handed over the presidency to Anthony S. “Tony”

Greene with Barber remaining as Chairman of the Board.

Ash Barber had worked long and hard to accomplish a turnaround and many chief executives in his position

would have liked to continue to direct the process until the results showed up in the financial report. But

Barber knew that to be fully effective the new system required a management style different from his own

and he wanted the new management to start under favorable conditions. The new management style

required much more delegation of decision-making responsibilities than Ash Barber was accustomed to

employ. And so, Barber made the decision to step down from the presidency. It was a classic example of

the way in which successful businesses must handle the problem of executive succession.

CONCLUSION

In 1976 “Ash” Barber joined W.B. Greene in retirement, and Tony Greene became Chairman of the Board as

well as President of Barber-Greene. On several occasions the company had been severely tested by its

environment during the leadership years of Harry Barber, Bill Greene and Ash Barber. But the company was

able to meet each challenge and move on to higher levels of achievement. It was able to do so because the

Barbers and the Greenes understood the underlying strengths of the business and were willing to make the

sacrifices necessary to maintain the long run health of the corporation. As Ash Barber put it, “Barber-Greene

was bigger than any of us – or our families.”

REFERENCES

1. Greene, W.B., “The Beginnings,” in Our First Five Decades, Aurora, Illinois, Barber-Greene Company,

1966, p.4.

2. Ibid. pp. 4-5.

3. Ibid, pp. 4-10.

4. Ibid, pp. 12-13.

5. This paragraph was added to the text by W.B. Greene in 1976.

6. Greene, W.B., “Our Second Decade … 1926-1936,” Our First Five Decades, Aurora, Illinois, BarberGreene Company, 1966.

7. Ibid., p.20. The fourth sentence in the quotation was added by W.G. Greene in 1976.

8. Ibid., pp. 20-21.

9. Ibid., p.21.

10. Turner, J.D., “Our Third Decade – 1936-1946,” Our First Five Decades, Aurora, Illinois, Barber-Greene

Company, 1966, pp. 28-29.

11. Barber, H.A., “Our Fourth Decade – 1946-1956,” Our First Five Decades, Aurora, Illinois, Barber-Greene

Company, 1966. Pp. 36-37.

12. Ibid.

13. Barber, H.A., “Our Fifth Decade … 1956-1966,” Our First Five Decades, Aurora, Illinois, Barber-Greene

Company, 1966, pp. 44-45.

14. Memo from H.A. Barber to Chief Executive Group, February 23, 1968.

15. “Budgets and Forecasts” Speech for District Managers meeting of October 14, 1968.

16. On August 30, 2975, the top management team consisted of the following eleven executive officers: H.

Ashley Barber, Chairman of the Board of Directors; Anthony S. Greene, President and Chief Executive

Officers; David B. Hipp, Vice President, Operations; Frank J. Merrill, Vice President, International; Merrill E.

Olson, Vice president, Sales; William A. Greene, Vice President, Administration and Secretary; Urban Hipp,

Vice President, Finance and Treasurer; James H. Rice, Vice President, Planning and Development; Donald W.

Smith, Vice President, Asphalt Construction Product Group; Jake R. Smith, Vice President, General Manager

Telsmith Division; Robert C. Johnson, Controller. In October 1975, David B. Hipp became Group Vice

President, Construction Machinery; Frank J. Merrill became Group Vice President, International Operations;

Merrill E. Olson became Group Vice President, Minerals Processing Machinery; and Donald W. Smith became

Vice President, Product Group Manager Construction Products.

17. Ibid

ANBHF Laureates

Our laureates and fellows exemplify the American tradition of business leadership. The ANBHF has published the biographies of our laureates and fellows.

Some are currently available online and more are added each month.