HERMAN MILLER COMPANY

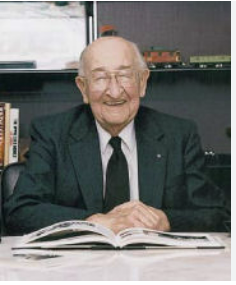

This is the story of a Christian business leader who proved by example that a highly successful business could be built on the principles of his faith. Between 1923 and 1961 Dirk Jan (D. J.) De Pree fashioned the Herman Miller Company into a highly profitable leader of the office furniture industry. He did it with a strategy of design leadership coupled with superior labor productivity. The key to that productivity was the implementation of a Scanlon Plan in 1950. Underlying the adoption of that plan was DJ’s belief that the relationship between management and labor must be covenantal rather than contractual. That philosophy was continued by two of DJ’s sons, Hugh and Max, after he gave up active leadership of the firm in 1961. In the late 1980s the company experienced explosive growth, and was ranked by the nation’s chief executives as one of the ten best managed companies in America.

Historical Significance

It is absolutely critical that voters, workers, business leaders, intellectuals, and religious leaders be familiar with the DJ De Pree story or similar examples of humanitarianism in business. What is at stake is nothing less than the survival of capitalism.

Capitalism is almost universally acknowledged to be the best economic system for promoting economic development. Even Karl Marx made that argument. Marx, of course, went on to criticize capitalism for the inhumane way it allegedly treated labor, and he predicted that once an economy had industrialized, the working class would rise, seize power and replace capitalism with a more humane system.

Few modern economists would agree with Marx. His analysis was deeply flawed and history has proven his vision of the steady “immiserization” of labor to be wrong. By 1990, the communist nations which had been inspired by Marx were in the process of importing capitalistic institutions in a desperate effort to revitalize their sagging economies.

Yet there remains a widely held belief that capitalism is inherently “inhumane” in an important sense. It is widely believed that capitalism generates material progress at the expense of individual growth and development. A great deal of economic theory supports this view by assuming that work is onerous and distasteful and that management has no interest in the workers beyond their production. This view that capitalism is an inherently selfish system is shared by religious groups. They tend to prefer some form of socialism which they believe is more likely to promote the altruism and humanism which they profess. In this they are joined by humanist intellectuals whose influence far exceeds their numbers because they write the books and editorials and produce the movies and television programs which the average citizen reads and watches. Thus capitalism has come to have a negative connotation to many Americans.

There are certainly countless examples which illustrate this negative view. If they are the only examples the public ever hears about, then capitalism is ultimately doomed. But there are those counter examples. Herman Miller is a case in point. In those counter examples lies the hope for the survival of capitalism. That is the future historical significance of the DJ De Pree story. A synopsis of that story follows.

Youth and Early Work Experience

Dirk Jan (D. J.) De Pree was born in Zeeland, Michigan in 1891. His father was a tinsmith who was also active in local politics. From the beginning religion was a major influence in D. J.’s family. His grandparents were Dutch Calvinists who had immigrated to Zeeland in the late 19th century. They sought a new home where they could not only earn a living but also live the full Christian life. D. J.’s parents were equally devout. They, in turn, raised a son for whom regular Bible study became a central part of his adult life. Persons of similar persuasion also settled in Zeeland so that D. J.’s social environment reinforced the teachings of his parents.

D. J. was baptized in the Reformed Church. As an adult he engaged in daily Bible study and began to question some of the doctrines of the Reformed Church. In the 1930’s he helped organize the Thursday evening meetings of a nondenominational religious group in Zeeland. In the 1950s that group became the new Baptist church and D. J. became a Baptist.

That streak of independence also showed up in politics. As a youth, D. J. became a Democrat in a town that was solidly Republican. (His father was also a Democrat). While D. J. was still too young to vote he was chosen to ride with Michigan’s Democratic Governor Elect in a victory parade, “because the town didn’t have enough adult Democrats to fill the car” [1, p. 112].

D. J. graduated from high school in 1909 and went to work as a clerk for the Michigan Star Furniture Company in Zeeland. The company had been formed four years earlier when a canning company went out of business, leaving an empty building. De Pree’s job consisted of general office work, taking orders from his boss and a secretary.

As a boy, D. J. had developed the reading habit and continued it as a young adult. It was because of that habit that he read an article on time management in Sunday School Times. Adopting the ideas in the article, he was able to finish his work at the company in half the normal time. He used the free time to study accounting and thereby position himself for advancement in the company. He also began reading the work of Frederick Taylor and other efficiency experts [1, pp. 20-21].

In 1914, D. J. married Nellie Miller, daughter of a local businessman. That marriage produced three sons, two of whom would eventually join their father in the business. The third became a college mathematics professor.

In 1923 D. J. decided to found his own business. With the help of a loan from his father-in-law he bought the Michigan Star Furniture Company. (The two purchased 51% of the stock.) He renamed the company Herman Miller in honor of his father-in-law [1, p.21].

The father-in-law was never active in the business. However, D. J. credits Herman Miller with adopting a policy of quality through the use of the best materials and best workers [1, p. 21].

For the rest of the decade Herman Miller continued to manufacture traditional furniture for homes. It struggled to earn a respectable profit, and remained a small company. There were no indications at that time that D. J. would become a distinguished American business leader. In fact, his father-in-law was convinced that D. J. was a poor manager with a very limited future [1].

Challenge and Response: The Product Quality Story

One cause of the company’s lackluster performance was the nature of the furniture industry. D. J. saw it as beset by “four evils” [1, p. 22]:

1. A buyer’s market

2. The four distinct seasonal markets

3. An “ear-to-the-ground attitude”

4. The sales force structure – sales were completely in the hands of independent contractors who worked on a 6 to 7% commission basis.

The buyer’s market depressed prices. The four distinct seasonal markets made it necessary to change production runs every three months. The “ear-to-the-ground attitude” meant that there was little scope for creative design because all manufacturers carefully watched what the others were doing and quickly copied or “knocked off’ any design ideas that looked profitable. The sale through independent contractors made it difficult for manufacturers to develop an effective, loyal sales force.

Herman Miller’s rise to distinction began with the problems created by the Great Depression which began in late 1929. The Depression caused a sharp drop in the demand for furniture. Herman Miller’s competitors reacted by cutting prices in a suicidal attempt to take the limited available business away from one another. D. J. knew that everyone would lose in the developing price wars. In addition, and more fundamentally, he knew that if he engaged in the wars he would have to sacrifice quality in order to lower costs. To him quality was a moral issue. To sacrifice quality would be to compromise his principles. His challenge was to find a way to stay in business without cutting prices. Time was short. In 1930 he estimated that the company would be bankrupt in a year unless he found a way out [1, p.22].

The 1930’s Strategic Gamble

D. J. had a general strategy. As he put it years later, “I had come to feel that my lot in life was to find a niche in which we could perform and no longer be a fabricator for brokers and buyers. That was the only plan I ever had” [1, p.22].

In the summer of 1930 a “providential event” introduced De Pree to a method of implementing that plan. An amateur furniture designer named Gilbert Rohde walked into Herman Miller’s Grand Rapids showroom. Rohde had ideas for a line of modern furniture. He had contacted other Grand Rapids furniture firms and had received no encouragement from them. Perhaps they were skeptical because Rohde had no actual experience in designing furniture. His background was that of an advertising and display illustrator [1, p. 24].

But D. J. had been praying for a miracle. He was convinced that Rohde was the answer to his prayers. And so he decided to abandon himself to Rohde’s ideas [1, p. 24].

Rohde’s proposal was a daring strategy. He would develop and sell new furniture designs with a contemporary look. He offered to design the furniture for a fee of $1,000 per group. That was far above the going rate of $300 per group in Grand Rapids at the time. Furthermore, D. J. didn’t have funds to pay the fee. Instead the two agreed on a 3% royalty fee [1, pp. 25-26].

Rohde’s first effort was introduced in 1930. It did not please D. J.. Rohde was asked to modify the design but refused to do so, saying that he would not compromise his work. Fortunately, the conflict was resolved when an influential and large New York furniture retailer ordered twelve sets of the furniture. D. J. conceded that Rohde was right and made a long-term commitment to let the designer follow his instincts [6]. The decision to trust the designer evolved into a Herman Miller philosophy which helped the company to attract and retain top design talent over the years that followed.

With his wisdom having been confirmed by the marketplace, Rohde proceeded to convert D. J. to the philosophy which would drive the company for the remainder of De Pree’s career. Rohde convinced De Pree that contemporary design had a moral dimension. It was a way of improving the quality of modern living. This view of the company’s business purpose appealed to the devout D. J.. As he put it years later,

- “We came to believe that faddish styles and early obsolescence are forms of design immorality, and that good design improves quality and reduces cost because it achieves long life which makes for repeatable manufacturing. By good design I mean design that is simple and honest. Materials should be used properly – would should be treated as wood, plastic as plastic and metal as metal. Things should look like what they are, with no fakery, no embellishment other than the material itself properly finished” [8, p. 8].

By 1934 sales of contemporary furniture were substantial and D. J. made another major strategic decision– the company would phase out the manufacture of traditional furniture. During the rest of that decade Rohde took the company into the production of seating furniture; he introduced sectional or unit furniture; and he took Herman Miller into the office furniture market with his Executive Office Group in 1942.

Rohde was also responsible for the company’s decision to market through independent show rooms in major cities. The decision to try this approach resulted from poor sales results in the department stores. D. J. and Rohde were convinced that the problem was a lack of knowledgeable salespersons. The showroom solved that problem by allowing Herman Miller to put trained, knowledgeable salespersons at the point of contact with the architects and designers who were the target customers [6].

George Nelson

Gilbert Rohde died in 1944. D. J. then launched a two-year-search for a suitable successor. Again, a “providential event” occurred. D. J. read an article in Architectural Forum on the use of walls for storage. Intrigued, he asked his New York sales representative, Jimmy Eppinger, to meet the author. It turned out that the article had been co-authored by the magazine’s managing editors, Henry Wright and George Nelson. Eppinger contacted Wright first, but Wright suggested he talk to Nelson, instead. Eppinger discovered that Nelson knew nothing about furniture design but did have a lot of thoughts consistent with Herman Miller’s philosophy. And so, Eppinger arranged a meeting between D. J. and Nelson in Detroit [1, p. 30].

- “They met in a local hotel restaurant and spent an evening talking about religion. Each was horrified by what the other believed about the Bible, although for Nelson the shock was softened by a steady stream of martinis” [1, p.30]. D. J. was intrigued and subsequently offered Nelson the Herman Miler design job in spite of the fact that Nelson had no experience with furniture. But Nelson refused on the grounds of lack of experience. D. J. then looked for alternatives but could find none. And so he returned to Nelson with a renewed offer. Nelson’s recollection of that meeting was as follows [2, p. 42].

D. J. said, “We did see a lot of designers who knew a lot about furniture…. We talked to them and looked at their stuff. They were all just terrible. All their furniture was awful…. So we’re back because we figured that all these experts being as bad as they are, we couldn’t do worse than get somebody who didn’t know anything. So how about it?”

Nelson was hired in 1945 and immediately went to work on a new line of furniture for all areas of the home. In a year and half his team was able to turn out seventy new pieces. Through 1988 that was the company record [2, p.43].

But Nelson wasn’t content to simply direct the design work. He took the initiative to develop advertising, sales literature and catalogs [2, p.43]. He assumed the responsibility for articulating the company philosophy and formulating a new marketing strategy [1, p.30]. In 1947, he conducted a survey of the furniture industry’s practices and prospects. The results were published in Fortune. They were also used to prepare a set of recommendations to Herman Miller’s top management for the company’s future.

Nelson’s importance to the company was once summed up by Hugh De Pree as follows [2, pp. 44-45]:

- George Nelson’s work gave us the foundation for a highly developed, coordinated design program…. George may have been the finest marketing man Herman Miller ever had, because he sensed trends and knew how to respond with solutions …. It was providential, fortuitous, plain lucky and the result of hard work that this working friendship between Herman Miller and George Nelson was formed, developed and carried on. At that time he was so important to Herman Miller that without him the company could well have ceased to exist…. George was not only a designer at Herman Miller but also a leader a consultant, a resource, a teacher. He contributed so much….

And, of course, the key to Nelson’s ability to contribute was D. J. De Pree’s amazing ability to allow him to do so. That ability to trust key people had previously shown up in D. J.’s relationship with Rohde. It would surface in the future in the cases of another key designer, Bob Propst and of D. J.’s sons, Hugh and Max.

Charles and Ray Eames

At the time Nelson introduced his first creations, he took the unusual step of urging D. J. to engage the services of a second designer, one who would be Nelson’s equal in status and pay. The new designer was Charles Eames. His work became known to Nelson through an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Nelson was so impressed that he lobbied D. J. to acquire Eames’ designs. D. J. was hesitant because of his concern for Nelson. He met with Nelson and is reported to have said [3]:

- We’re just getting ready to introduce your first products to the market. We’re not a large company. We’ll never pay much in royalties. Do you really want to share this small opportunity with another designer?

Nelson’s legendary reply was something like [3, p. 67]:

- Charles Eames is an unusual talent. He is very different from me. The company needs us both. I want very much to have Charles Eames share in whatever potential there is.

Nelson subsequently had second thoughts because of the compensation issue but was able to overcome them and become a supporter of Eames [2, p.44].

Nelson’s insistence on sacrificing potential personal income for a bigger goal became one of Herman Miller’s “tribal stories” in the years that followed. It was told repeatedly to inform new employees and remind the old timers that Herman Miller was a company where heroes and heroines put creativity first, where people took the long view, and where the joy of creating was as important as earning a living.

Eames quickly paid back the company’s investment in him. As predicted, his designs did well in the marketplace. And in 1948 he made a significant contribution to production methods by applying airplane manufacturing methods and materials in the production of his molded shell chair design. By the late 1950s Eames’ designs were Herman Miller’s major programs [2, pp.46-47]. And in 1985 the World Design Congress named Eames the most influential designer of the century [12].

The Office Furniture Emphasis

Nelson was particularly interested in the design of office furniture. Office furniture also appealed to D. J. because that particular market niche appeared less prone to price-cutting and more amenable to the kind of quality strategy that was evolving at Herman Miller. Consequently, the company’s expansion took place in the office arena. During the 1950s Herman Miller introduced several successful new office products. But the major developments awaited the establishment of the Herman Miller Research Corporation under Robert Propst.

Organized Research

One of Gilbert Rohde’s lasting contributions was his philosophy that Herman Miller should devote itself to, “researching and answering basic human needs in the home and business environments” [11, p.2]. D. J. embraced that vision. During the 1950s he approved several initiatives to expand and improve upon the company’s research effort. In 1955 Herman Miller established a “tech center” to improve the company’s designs and production methods [11, p.4]. Then another “providential event” occurred. In 1958 D. J. was visiting his third son, John, in Colorado and heard about a Denver inventor/designer named Robert Propst. De Pree sought out Propst. He was impressed and encouraged Hugh De Pree to follow up. Thus began a two-year dialogue between Hugh and Propst that resulted in the establishment of the Herman Miller Research Corporation in 1960.

The research corporation was directed by inventor Propst. Its purpose was to research the furniture needs of the modern office and to enable Propst to explore other ideas which might be of interest to the company. Its operating premise was that office productivity could be improved by the proper integration of people, machines and work processes. Its first decade was spent studying what office workers actually did and how the office environment could be changed to facilitate the work. As told in a recent company history [11, p.7]:

- Robert Propst had to put aside all the assumptions that had been made about the office during its brief history. Instead he asked questions: about, for example, the exponential rate of change in the office environment. Propst and his research team asked how an office could aid information workers in a world that offered too much information to handle. They studied the fact that more and more professions required offices and that each discipline required a different environment to work effectively…. They recognized that display triggered recall and asked themselves how an office with too much information pouring into it could keep information out in the open. They examined the way work travels in the office, the way conversations are held, and the conflict between privacy and the need to be involved.

The result of that research was the introduction of the Action Office system in 1968. It was not immediately successful, but it continued to evolve after 1968. One of the later versions of the Action Office served as the basis for the company’s sudden, explosive growth in sales in 1977. And in 1985 the World Design Congress named the action Office the most significant industrial design since 1960 [12].

The introduction and ultimate success of the Action Office took place under the leadership of Hugh De Pree. By that time D. J.’s role was strictly symbolic. But the groundwork for the success had been laid by D. J.’s decision to seek out Propst.

Challenge and Response: The People Story

Between 1930 and 1950 Herman Miller’s distinction was achieved in the area of business strategy and its implementation. But throughout that period D. J. De Pree was bothered by two concerns regarding the work force. One concerned quality and productivity and was to be resolved in 1950 by the adoption of the Scanlon idea. The other concerned the quality of work life and would be resolved by the creation of an amazingly humane corporate culture.

The Scanlon Plan and Participative Management

The Scanlon Plan came to Herman Miller as a result of another “providential event”. Here is how Ralph Caplan summarized the story [1, p. 115].

- In 1950, D. J. and Hugh De Pree went to a meeting of the Grand Rapids Furniture Manufacturers Association to hear a Michigan State University professor named Carl Frost speak on cost accounting. Frost, however, didn’t talk about accounting; he talked about something called the Scanlon Plan, and during the drive back to Zeeland, the De Prees decided to look into the matter…. Frost agreed to set up a Scanlon Plan at Herman Miller, with the stipulation that the De Prees themselves participate and share in the bonuses.

Herman Miller’s Scanlon Plan was installed in May 1950. At that time the company employed 120 people, 90% of whom were production workers. The new plan applied strictly to the production workers [18, p. 50]. The plan attempted to boost production worker productivity by getting them to participate in decision-making and providing rewards (in the form of a bonus) for projects and practices which they initiated and which boosted productivity. The Scanlon idea and its application at Herman Miller are discussed in greater detail in the Appendix.

The Scanlon Plan, or as many put it the Scanlon Idea, became and continues to be a cornerstone of Herman Miller’s success. On two occasions, as chronicled in the appendix, there were major changes in the plan, but the basic philosophy remained the same. The changes were forced on the company by developments in the business environment. The company was able to successfully adapt to the changes because it correctly viewed the Scanlon Plan not as a rigid recipe but rather as an idea capable of being implemented in a variety of forms depending upon the circumstances.

Beyond the Scanlon Plan – The Covenantal Relationship

The process of installing the Scanlon Plan energized D. J. De Pree’s long dormant vision of creating a fulfilling workplace. He began to devote time to thinking about other ways of raising the level of interpersonal relationships at the company. He shared his thoughts with his two sons, both of whom were managers at the company. Together the three worked out the elements of what they later referred to as the “covenantal relationship” at Herman Miller. Many years later Max De Pree explained it this way [3, pp. 50-51]:

- Broadly speaking, there are two types of relationships in industry…. The contractual relationship covers the quid pro quo of working together…. Covenantal relationships, on the other hand, induce freedom, not paralysis. A covenantal relationship rests on shared commitment to ideas, to issues, to values, to goals, and to management processes. Words such as love, warmth, personal chemistry are important. Covenantal relationships are open to influence. They fill deep needs and they enable work to have meaning and to be fulfilling…. Covenantal relationships enable corporations to be hospitable to the unusual person and unusual ideas. Covenantal relationships tolerate risk and forgive errors.

The covenantal concept was introduced at Herman Miller by D. J. and elaborated by successor management. The basic idea originated in a “providential event” in 1927. It began with the death of the firm’s millwright, Herman Rummelt. D. J. went to Rummelt’s home to pay his respects to the widow. She welcomed him and proceeded to talk about her husband while showing D. J. some of the man’s effects. And suddenly, D. J. had a revelation. Here is how he remembered it [13, p.3]:

- There were several things about Herman Rummelt that I thought were unusual. One was the handicrafts that he made – primarily for his wife – and that was the first thing she showed me…. Then the next thing she showed me was this sheaf of papers with his poetry in his own handwriting. Then she began to tell me about one of the men who was in his department who had been a machine gunner in World War I and had killed a lot of Germans, and felt he was a murderer and he was going to Hell because of that. Well, Herman Rummelt took time to spend with this man; he was the night watchman and between rounds would show him from the Bible that there was reconciliation and forgiveness.

So I saw this man with an interest in the souls of the people. He was a craftsman. He wrote poetry. Here were three sides of a person besides his job of keeping that line shaft in good shape.

That was the morning he died. Later, after the funeral, as I walked the block and a half from the church to my house, I felt that God was dealing with me in this matter of my attitude toward the workers in the plant, and I began to realize that we’re all alike. Because here was a man that did these things that I couldn’t do, or I wasn’t doing. By the time I got home, I had decided that we were all extraordinary, and this changed my whole attitude toward what we call ‘labor’…. These people were my peers.

D. J. implemented that new vision in little ways over the next several decades. Then the discovery of the Scanlon Plan allowed the company to make substantial progress in establishing the covenantal relationship after 1950. Subsequently, D. J., Hugh and Max established a company culture with the impressive set of covenantal rights listed in Table 1.

Successor Management

In 1960, D. J. contracted an illness which cut short his career. He stepped down as CEO in 1961. When he recovered, there was no longer room for him as CEO. And so he became active in the Gideon Society and served as their president. The new management team consisted of sons Hugh and Max. D. J. continued to provide input and inspiration as chairman emeritus but the sons ran the company. Under Hugh and Max the company grew and changed but the Scanlon Plan and the covenantal relationship remained in place in spite of several serious challenges.

The challenges led to two changes in the Scanlon Plan as explained in the Appendix. Prior to those changes the De Prees had introduced an employee stock ownership plan in 1970. It provided incentives for employees to buy stock and included a bold provision allowing any employee to sell the stock he or she owned or a portion of it at any time. Max De Pree once observed that without that right, the employee doesn’t have true ownership [5].

An even more impressive commitment to the employees was made in the 1980s when the company responded to the general threat of a hostile takeover. Most companies of that decade protected their top management employees with so-called “golden parachutes”. At those companies other employees were left to fend for themselves. In contrast, Herman Miller adopted a “silver parachute” policy by means of which all employees were afforded financial protection in case of a hostile takeover.

Table 1

Employee Rights at Herman Miller

1. To be needed

2. To be involved

3. To be cared about as an individual

4. To receive fair wages and benefits

5. To have an opportunity to do one’s best

6. To have the opportunity to understand

7. To have a piece of the action in the form of productivity gains, profit sharing, ownership appreciation and seniority bonus

8. To have the space to realize one’s potential

9. To have the opportunity to serve

10. To have the gift of challenge

11. To have the gift of meaning.

Source: Max De Pree, Leadership is an Art

Conclusion

In the 1980’s Herman Miller finally gained the nationwide recognition for management excellence that it deserved. The record-breaking book, In Search of Excellence [17], cited the company as an example for others to follow in 1982. The book The 100 Best Companies To Work for In America [10] included Herman Miller on its list. The book The Best Companies For Women [19] picked the company as a leader in that category. Surveys of corporate leaders undertaken by Fortune magazine began to pick up Herman Miller as one of America’s most admired corporations (in 1989 it ranked 9th overall).

In 1989 Max De Pree, by then retired from active management, published his widely acclaimed summary of Herman Miller thinking [3]. In the preface of the book, nationally recognized management professor James O’Toole answered his own rhetorical question, “Why study Herman Miller?” with these reasons:

1. Its profitability — $100 invested in the company’s stock in 1975 would have been worth $4,854.60 in 1986 (an annual compounded growth rate of 41%).

2. Its heavy spending – it outspends its industry rivals on research two to one and that spending development has made it the leader in terms of introducing significant new products.

3. Its high labor productivity.

4. Its success in getting employees to act as if they owned the place.

5. Its integrity.

O’Toole refers to the company as it was in the 1980’s. As we have seen the company at that time was the result of successful responses to a series of challenges over a number of years. Hugh De Pree once summarized that history as follows [2, p. 153]:

- There is a pattern in the affairs of a company. The principles and beliefs, encounters and events, people and performance – all continually design and redesign the business. At Herman Miller part of this pattern is the series of crises and fortuitous encounters that have played a major role in the design of this company…. These crises were, first the definition of the problems in the furniture industry; second, the sudden death of Gilbert Rohde; third, the vision that each person is extraordinary and can contribute to the business; fourth, the change from representation in the market to an integrated sales and marketing program; and fifth, the rapid movement from residential furniture to systems and furniture for work in the office, factory and health care facilities.

D. J. De Pree’s years of leadership covered the first three crises and their resolution. Hugh and Max De Pree were the executives who handled the last two. But in all five cases the success in dealing with crisis must be credited to the corporate culture which D. J. fostered.

Perhaps author Ralph Caplan summed up D. J. De Pree’s career best when he said, “Some corporation heads have been so dominant as to leave little distinction between the man and the firm, but De Pree was not one of them…. (W)hatever uniqueness there is in the Herman Miller Corporation stems directly from the unique combination of events and people whose influence he was open to…. The operative word is OPEN, for De Pree was as much influenced as influence. His control of the company did not lie merely in imposing his will on subordinates…. Rather it lay in his performance as selective conduit for the ideas of others. As it happened, these others were designers, and that made all the difference – it led to Herman Miller’s hegemony in the field of design” [1, pp. 17-18].

Or perhaps the last word should be that of Max De Pree when he observed, “There are two ways of competing in this business – you can nickel and dime the competition to death, or you can take giant steps that distinguish you from them. But the only way to take giant steps is to have giants. D. J.’s principal strength was the ability to abandon himself to the strength of unusual people. Of course, we all know that one of the really important business skills is the ability to delegate, but D. J. went much further. Being abandoned to someone else’s strength is a giant step that goes beyond delegation – that is when you get super performance from people” [1, p. 18].

Appendix

This appendix provides a more detailed summary of the Scanlon Plan and its use at Herman Miller.

The Scanlon Plan

Named after Joseph N. Scanlon (an accountant, steelworker and steel union local president), the plan is based on the philosophy that if a firm fosters and uses suggestions from its employees and rewards them for those efforts, the company’s profitability should be enhanced and the employees should benefit through increased pay. There are four basic elements of a Scanlon Plan:

1. The ratio;

2. the employee bonus;

3. the production committee; and

4. the screening committee.

The ratio is the standard used for evaluating the performance of the firm. In its simplest form, the ratio compares the total (all wages, salaries and benefits) cost of employee compensation to the total market (sales) value of the firm’s production. The ratio is:

Total employee cost

Total value of production

For instance, the ratio might be .50/1.00, which means that there is a $ .50 labor cost for $1.00 of production value.

Once the ratio is set, the employee’s monthly bonus is based on a reduction in costs below the present ratio. For example, a company might be using a monthly bonus procedure that distributes the first 25 percent to a reserve account to reimburse the firm if the actual ratio rises above the present ratio in future months. Seventy-give percent of the remaining funds (56.25% of the total bonus) is paid to all employees on a monthly basis and 25% (18.75% of the total bonus) goes to the company as its share of the bonus pool. The monthly bonus might be distributed as illustrated in Table 2.

The purpose of the bonus is to encourage employee suggestions for improvements in the production process. The size of the bonus depends upon savings in labor costs below the present ratio. To facilitate employee suggestions and teamwork and develop cost saving ideas, a production committee is established in each department or other appropriate unit of the company. The committee is composed of one management representative, normally the department/unit supervisor and one or more representatives elected by the non-managerial employees in the department/unit.

Each production committee typically has two major responsibilities. First the committee encourages employee suggestions to increase productivity, reduce cost, improve product quality and enhance the functioning of the entire organization. Second, the committee is charged with the responsibility of following through on employee suggestions by taking appropriate action on the ideas.

Under the Scanlon approach, employees do not receive any individual bonuses for their suggestions. Ideas that generate bonuses are shared by everyone in the organization. The purpose of this form of incentive is to encourage teamwork and collegiality among all employees. Explaining this approach to incentive pay Carl Frost wrote, “the central idea is that the person doing the job will have good ideas with people who do the same or similar work, and will encourage other people to make suggestions by sharing ideas with them” [4, p. 7].

Suggestions coming to the production committee that require either a large financial investment to implement or that cut across department lines and require interdepartmental action to implement are normally referred to a second committee called the Screening Committee. The Screening Committee consists of the top members of management and an equal or greater number of non-managerial employees that are elected to the committee. In addition to reviewing suggestions referred to them by the production committee, this committee reviews the financial data relating to the monthly bonus, announces the bonus (if earned for the month) and provides the supporting information, identifies company problems and encourages employee suggestions, and discusses external trends and problems that can impact the firm.

The production committee will typically meet twice a month, while the screening committee normally meets on a monthly basis. The success of a Scanlon Plan will hinge to a large extent on these two groups.

Herman Miller and the Scanlon Idea

In 1950, Herman Miller’s sales volume was less than $2 million a year and it employed about 120 workers. Approximately 90% of the employees were in direct production where they engaged in piecework and were paid on a piece rate basis [15]. Some of these rates were set too low while others were too high. Describing this situation, Jay DeHaan (a long-time employee) remembers: We had minutes for every operation that we did. The more chains you did, the more minutes you got…. So your pay was based on speed, what you could do.

Well the company always had problems with these rates, these piece rates. Some were good, some were bad. If you’d get good rates you could really make good time, and of course everyone would want to get the ‘good’ chains…. And then there were rates that you had a terrible time making. There was a lot of inequality. Of course if a person had an idea of how to do it better and faster, he didn’t share that because it benefited him … to be faster than everyone else [13, p. 4].

In an attempt to be “better” by making the product as well as they designed it, Herman Miller installed its version of the Scanlon idea in June 1950. This plan had four primary principles that applied to all employees:

- 1. Identity – everyone understanding the business – its history, its values, its gals and objectives, and the critical issues it faces – and how he or she can responsibly take part. Essentially, identity is a matter of literacy, of being well-informed in order to be effectively involved. It is one’s feeling a part of the business because one has been empowered to be a part of it. It is merging personal goals with organizational goals, the organization becoming the vehicle for achieving those goals and gaining the rewards that ensue.

2. Participation – everyone working together responsibly to accomplish shared business goals and objectives. Essentially, participation is a matter of the opportunity for ownership, of feeling responsible to join with others as a positive influence in order to get the necessary work done. It is responding responsibly because one knows her or his stake in the business.

3. Equity – everyone receiving a fair return for the investment of his or her time and talents in helping meet the organization’s goals and objectives. Essentially, equity is a matter of accountability, of sharing in the results of performance, of willingly being responsible for one’s actions an accepting the consequences for them. It is getting a reward because one has risked involvement in the business. At Herman Miller, equity is not limited to employees but embraces other stockholders, customers, dealers and suppliers as well – all of whom invest to some degree or another in the company and deserve an equitable return.

4. Competence – everyone being capable in his or her area of responsibility. Essentially, competence is a matter of commitments, of being motivated to cooperate with others to contribute to the limit of one’s potential to effect positively the welfare of the business. It is doing well what needs to be done because one knows that that is essential both to his or her welfare and tot he welfare of the business [15].

The basic elements of Herman Miller’s version of the Scanlon Plan were: a participative structure, a bonus system to replace piece rates and a communication system. The participative structure included a series of production committees to review and act upon employee suggestions and a screening committee to review, analyze evaluate and make recommendations concerning both employee suggestions submitted to them and the total operation of the company.,

The bonus system was based on the productivity of labor. The entire difference between labor earned (direct and indirect labor allowances on each product produced) and actual labor costs (sum of wages, salaries and benefits) was paid as a bonus to all participating non-field sales employees in direct proportion to their base pay.

The actual bonus system used differed markedly from our earlier example. In our example, a portion of the bonus pool was immediately set aside as a reserve and the company shared with the employees in the remainder of the pool. The Herman Miller system allocated the entire amount to eligible employees.

The communication system involved a combination of group monthly meetings and printed information. Early in the month a day (called the Scanlon Day) was designated to conduct a series of meetings to review the company’s previous month’s performance. This was followed the next day by the distribution of the actual bonus checks and documentation explaining how the bonus was calculated. Between the monthly meetings, written information was distributed to keep employees abreast of their performance.

For over 25 years, the original Scanlon Plan worked extremely well, and the company experienced steady growth. Sales were approaching $50 million by the mid-70’s, the work force had grown to over 550 employees and bonuses were paid on a regular basis [15]. The best bonus year was 1974, when the bonus averaged 22.83% [18, p. 51].

Then a major change occurred in the environment. From 1976 to 1979, the company experienced very rapid growth. Sales increased from $50 million to almost $175 million and the total work force grew to over 2,500 people [15]. This spurt in growth had, to a large measure, been the result of employee cost-savings suggestions that allowed the company to reduce prices by 10% on its Action Office Systems products. This price cut came at a time when other major competitors were raising prices and resulted in a major increase in demand for Herman Miller’s products.

Scanlon ’79

Top management recognized that the company had growth faster than their ability to manage and control it. In addition, almost 50% of all employees were employed in areas other than direct production [18, p. 52]. This segment of the work force had very little input into the suggestion system, even though they shared with the other employees in the monthly bonuses. In general, many employees found the bonus system calculation confusing and did not have a great deal of faith in the system. Expressing the general feeling of the employees concerning the bonus system, Deb Exo (Tackboard Machinest Coordinator) remarked, “I can’t see where I’m making a difference. Especially if I’ve worked exceptionally hard or I’ve really put out; or I’ve done the best I could with the things I could control, and I still receive a poor bonus – why [13, p. 15]?” Recognizing their problems, top management formed an ad hoc committee of 68 people in 1978 [15]. These employees represented a wide spectrum of the company and were charged with the responsibility of assessing the Scanlon Plan and recommending changes that would make it relevant for both the present and the future. In January 1979, the committee’s recommendations were presented to the employees for their consideration. A company-wide vote was taken, and over 95% of all employees approved the recommended changes in the Scanlon Plan [18, p. 54].

Scanlon ’79, as it is called by the employees, was composed of a new process of participation and communication, and a new bonus formula. To facilitate cooperation and communication, the production committees and the screening committee were replaced by a work team, a caucus and a council. These three groups were set-up throughout the entire company.

The work team meets regularly and consists of a manager’s supervisor and the immediate employees in the unit. The work team deals with employee suggestions/problems, reviews the unit’s plans and goals and evaluates the unit’s performance.

The caucus is actually a peer group made-up of employees at the same level within the organization, or with similar jobs in the same department/area. If suggestions or problems submitted to the work team are not resolved to an employee’s satisfaction, they can be resubmitted to the caucus. In addition, the caucus acts as an employee support group and elects representatives to the area council.

Each department/division throughout the company has a council. The council’s primary purpose is to discuss and review employee suggestions dealing with topics such as the operation of the Scanlon plan, customer service, productivity, and employee safety and work methods. The council is headed by a director or vice president and includes that person’s work team plus elected employee representatives.

In addition to creating the work team, caucus and council to improve on the bonus system through a more comprehensive bonus formula. Under this new plan both cost savings and performance were brought into consideration. Performance is measured against the annual business plan and includes customer service and the effective use of financial capital, materials and human resources. Targets are set for each of these four areas and when they are exceeded the employee bonus is increased. Cost savings is also measured and calculated based on a yearly goal. For a more detailed and comprehensive discussion of both the original Scanlon Plan and Scanlon ’79, see “Labor-Management Cooperation – The Scanlon Plan at Work,” by Judith Ramquist.

Scanlon in the 1980s

Rapidly changing market conditions during the early and mid 1980’s necessitated another major review of the relevancy of the Scanlon Plan. Once again, the company’s employees were asked to conduct a thorough review of the plan and to advance recommendations for renewing the process.

In 1988, a modified process was implemented. It included changes in both the suggestion system and the calculation of the bonus.

Under the revised suggestions process, work team leaders receive employee suggestions. If the suggestion can be evaluated and implemented within the department/unit, then no additional steps are needed except for reporting the cost-saving/cost-avoidance results to the newly created Suggestion System Office. If the suggestion involves another department/unit then it is forwarded to the Suggestion System Office.

The newly established Suggestion System Office is headed by a manager whose role is to organize and direct the suggestion process. In addition, the manager chairs a newly formed Review Board composed of directors from different areas of the company.

The Review Board, meeting weekly, reviews and assigns suggestions submitted from the Suggestion System Offices and follows through on them to make sure that prompt action is taken. Any employee not satisfied with the decision made on his/her suggestion can appeal that decision through the Review Board.

The purpose of both the Suggestion System Office and the Review Board is to increase the efficiency of the suggestion process. It was felt that the new suggestion process would present a more responsive mechanism for revising and quickly acting upon employee suggestions.

The bonus system was also revised in 1988. The bonus is now calculated quarterly by an Equity Committee, and is based on both profitability and quality. Two-thirds of the bonus is paid from increased profitability as measured by growth (average increases in net sales and operating income over the same quarter of the previous year), asset use (improvements over $2 of sales for every $1 of assets annually or fifty cents for every dollar of assets quarterly) and cost savings (20 percent of net savings from implementing suggestions, plus an additional 20 percent on all cost savings over a predetermined goal). One-third of the bonus is based on improvements over the previous year in product quality and the quality of service. Improvements in quality are measured by responses from both customer and dealer surveys. The total of the five measurements divided by the participating payroll cost equals the bonus figure for the quarter [13, p. 25-27].

This article was written By Dr. Richard E. Hattwick, Dr. Robert L. Olcese and Dr. Michael T. Pledge.

*Copyright 1990. The American National Business Hall of Fame. All rights reserved. No portion of ANBHF may be duplicated, redistributed or manipulated without the expressed permission of the ANBHF.

REFERENCES

1. Caplan, Ralph. (1976). The design of Herman Miller. New York: Whitney Library of Design.

2. De Pree, Hugh. (1986). Business as Unusual. Zeeland, MI: Herman Miller, Inc.

3. De Pree, Max. (1989). Leadership is an Art. New York: Doubleday.

4. Frost, Carl F., Wakely, John H., & Ruh, Robert A. (1976). Scanlon Plan for Organization Development: Identity, Participation, and Equity. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.

5. Hattwick, Richard E. (1990, July 6). [Interview with Max De Pree at Herman Miller, Inc., Zeeland, MI].

6. Herman Miller, Inc. (19810. Gilbert Rohde: The Herman Miller Years. Zeeland, MI: Author.

7. Herman Miller, Inc. (1989). 1989 Annual Report. Zeeland, MI: Author.

8. Knoll, Florence. (1975). A Modern Consciousness: D. J. De Pree. Washington: Smithsonian Institute Press.

9. Labich, Kenneth. (1989, February 27). Hot Company, Warm Culture. Fortune.

10. Levering, Robert, Moskowitze, Milton, & Katz, Michael. (1984). The 100 Best Companies to Work For in America. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

11. Maasen, Lois. (1989). What is truth in design? Herman Miller Magazine, pp. 2-11.

12. Miller, Herman. (1989). Herman Miller is built on its people, research and designs (loose handout 8604-232). Zeeland, MI: Author.

13. Miller, Herman. (1988). Renewal (abridged ed.). Zeeland, MI: Author.

14. Miller, Herman. (1989). Corporate Values. Zeeland, MI: Author.

15. Miller, Herman. (1989). Participative management at Herman Miller. Zeeland, MI: Author.

16. O’Toole, James. (1985). Vanguard Management. New York: Doubleday and Company.

17. Peters, Thomas J. & Waterman, Robert H., Jr. (1982). In search of excellence. New York: Harper & Row Publishers.

18. Ramquist, Judith. (1982, Spring). Labor-Management Cooperation – The Scanlon Plan at Work. Sloan Management Review, 23, 3.

19. Zaitz, Baila & Dusky, Lorraine. (1988). The best companies for women. New York: Pocketbooks.

ANBHF Laureates

Our laureates and fellows exemplify the American tradition of business leadership. The ANBHF has published the biographies of our laureates and fellows.

Some are currently available online and more are added each month.