Tom’s of Maine

GREEN COMPANIES: TOM’S OF MAINE

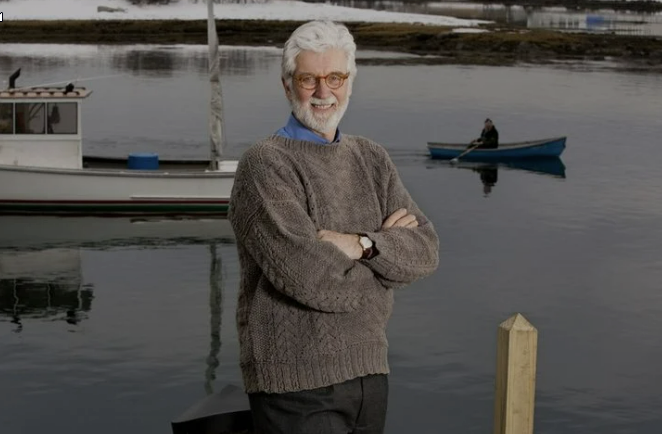

By

Edmund R. Gray

And

Kimberly S. Petropoulos

Tom’s of Maine is a living, breathing – and profiting- proof that a

Business enterprise can be good for the earth, good for society,

Good for its employees, and good for its shareholders

—- Tom Chappell (1993)

Tom’s of Maine, located in Kennebunk, Maine, is a manufacturer of all-natural personal care products. The family-owned company was founded by the husband and wife team of Tom and Kate Chappell. The couple started the company because they were unable to find natural personal care products for their family to use and consequently believed that there must be a market for such products.

All company products are made from ingredients whose ultimate source is nature. They are free of artificial colors, sweeteners such as saccharin, synthetic preservatives, flavors and fragrances. Additionally, they contain no animal by-products and are not tested on animals (Tom’s of Maine, undated).

Sales of company products are strongest on the East and West coasts. Target customers are active, health-conscious adults who read labels, are involved in their communities, and value education.

Company sales were approximately $40 million in 1999. Its flagship product was toothpaste which historically accounted for 60% of its revenues with a national market share of about one percent. The U.S. toothpaste industry in 1999 was a $1.7 billion per year business. Market leaders were Procter and Gamble’s Crest and Colgate-Palmolive’s Colgate brands (Popovich).

At the beginning of 2000, Tom’s had 120 employees but found itself in a self-imposed hiring freeze because of its heavy investment in new line of alcohol-free cough, cold and wellness products. With the introduction of the new line, the company had 150 new products. In addition to toothpaste and wellness products, the company also produced deodorant, flossing ribbons, mouthwash, soap, shampoo and shaving cream.

HISTORY

In 1968, Tom and Kate Chappell left Philadelphia and their positions in the corporate world for Kennebunk, Maine where they “moved back to the land” and experimented with natural food and personal care items, and other environmentally friendly products. Two years later, with a $5,000 loan from a friend and a single product named Clearlake, they started Tom’s of Maine.

Clearlake was the first non-phosphate, liquid laundry detergent offered for sale in the U.S. The product came in refillable containers that were labeled with postage-paid mailers to facilitate customers returning them for re-use (Tom’s of Maine, undated).

The company inaugurated its signature all-natural personal care product line in 1973 with soap, shampoo and skin lotion. Natural toothpaste was also introduced in 1973. other products followed, first with baby shampoo, then deodorant , mouthwash and shaving cream. Early on, Tom’s products were distributed principally through health food stores. From the very beginning the company shunned the traditional practice of testing products on animals.

By 1981 sale had risen from nothing to $1.5 million. Having achieved this plateau, Chappell wanted to take his products into the mainstream market. To accomplish this, he knew that he needed to add professional talent to manage the growth of the new accounts, more complex distribution channels, and a burgeoning advertising budget. Hence, he added a few new board members with business acumen and then hired several experienced marketing executives along with some young MBA’s. A strategy of aggressive growth by expanding beyond health food stores to big supermarkets and drugstore chains was implemented. This resulted in a 25% growth rate over the next two years to approximately $ 2 million in 1983.

The rapid growth strategy exposed a germinating conflict between Chappell and the new professionals. For instance, the new “MBAs” tried to convince Chappell to add saccharin to his toothpaste to sweeten it, thus making it more palatable to the mainstream market. As he perceived it, they were promoting decisions based on the numbers rather than adhering to his vision of commitment to natural products. Recalling this time in company history, Chappell noted that , “Our values were pushed to the margin. Growth and profit dominated business planning.” (Chappell, 1993, p. 25).

As a consequence of these tensions, Tom Chappell found his company less and less fulfilling and began to search for inspiration elsewhere. He remembers confiding to two old friends that he was considering going to theological seminary and becoming an Episcopal minister. In retrospect perhaps Tom’s of Maine was his ministry.

In 1988, Chappell enrolled on a part-time basis at Harvard Divinity School. For the next three years, he spent two and a half days a week in Kennebunk running the company and the remainder of the work week in Cambridge. At Harvard, he studied the writings of the great moral and religious philosophers, such as Immanuel Kant, Martin Buber, and Jonathan Edwards, and tried to relate their ideas to business in general and Tom’s of Maine in particular.

Upon returning to Tom’s full-time, his first priority was to codify the company’s mission and values. Over an intense period of three months, first with the participation of the Board of Directors and later the entire company staff, two key documents – “Statement of Beliefs” and “Mission Statement”- were developed and approved by all participants.

Nineteen-ninety-three and ninety-four were trying years for Tom’s of Maine. The company’s newly introduced deodorant did not perform consistently and was prone to breakage. Upon discovering these problems, Chappell ordered a recall at a cost of $400,000 to the company and apologized to the company’s customers. To help cover the cost the advertising budget was slashed 25 percent. The incident came to be known throughout the company as the “deodorant debacle” and led to a significant revision of the company’s development process. (McCune, 1997).

The product recall along with stiffer competition from the major brands (e.g. Crest and Colgate) that had introduced their own healthy baking soda toothpastes led to the company’s first loss — $400,000 in fiscal 1994. In response, Chappell hired additional salespeople with major brand experience, added a former Pepsi Company executive to the board, and introduced new toothpaste flavors along with an entire line of fruity-flavored children’s toothpaste. Earnings, as reported by Forbes, recovered to $650,000 in 1995 (Forbes, Vol. 156).

In 1996, Tom and Kate Chappell seriously considered selling the company in order to achieve financial freedom and pursue other interests. Working with their investment banker, they established specific criteria for the acquisition based on the company’s beliefs and mission. They insisted that price not be the controlling factor in the decision but rather the dedication of the acquiring firm to the company’s stated values. Six potential purchasers were identified but all found the acquisition criteria too restrictive and dropped out of the bidding. In the end, the Chappells found that they could not sell their business without compromising their own values, which they were unwilling to do (Chappell, 1997).

Representing a sizeable investment for the company, Tom’s introduced, in 1999, a major new line of wellness products. The new line included natural echinacea tonics, nasal decongestants, cough and cold rub/muscle balm, and liquid herbal extracts. These products were developed by an interdisciplinary team of pharmacognosists (natural medicine specialists), herbalists and chemists put together by the company. To assure the quantity and quality of botanicals needed, the company purchased its own certified organic farm in Saxton Rivers, Vermont. Additionally, the company contracted with other organic growers for the required ingredients it did not produce on its farm. The new line was distributed through health food stores in the U.S., Canada, and the U.K. (Tom’s of Maine information sheet).

BUSINESS PHILOSOPHY

Tom Chappell grew up in Western Massachusetts surrounded by farms and fields and his family enjoyed frequent vacations in Maine. As a result of this environment, early in life he developed a love of the land and a sensitivity to the natural environment that eventually became a vital part of his business philosophy. The fact that he was raised in the Episcopal church and that his father was a successful entrepreneur also played a role in the development of his personal values. Chappell once said, “When you have a family business, it becomes the DNA of every member of the family.” (May,2000).

Tom and Kate founded Tom’s of Maine to produce natural products that they could not find in the marketplace. From the beginning, the founders expressed their strongly held personal values of respect for both people and nature through their company. But Tom Chappell was also a highly competitive businessman who wanted to grow a large and successful company. With the rapid growth of Tom’s of Maine, the Chappells’ goals and values came into conflict with the company’s emerging professionalism and eventually led to Chappell’s enrollment at Harvard Divinity School. While at Harvard he came to the conclusion, as his friend had suggested several years earlier, that his true ministry was his company. There, he also learned a language that would allow him to “debate his beancounters.” (Chappell, 1993, p.16).

Early in his academic program Chappell studied the work of Martin Buber, the twentieth-century Jewish philosopher who argued that man can have two opposite attitudes toward others, leading to two distinct types of relationships. In one, the “I-It” relationship, people treat other people as objects and expect something back from each relationship. In the other, the “I-Thou” relationship, the individual relates to others out of respect, friendship, and love. In other words, we either see others as objects to use for our selfish purposes or we honor them for their own sake. Chappell concluded that he and Kate had instinctively been doing business using the I-Thou relationship and his professional managers were behaving in terms of the I-It model.

Chappell was also deeply influenced by the writings of eighteenth-century American philosopher Jonathan Edwards. Edwards believed that an individual’s identity comes not from being separate but from being connected or in relationship to others. Chappell began thinking of Tom’s in this light, perceiving it not simply as a private entity but in relation to other entities, i.e. stakeholders such as employees, customer, suppliers, financial partners, governments, the community and eve Earth itself. He concluded that the company had obligations to each of these that could be defined in terms of time, money and priorities.

The ideas of Buber, Edwards and other philosophers became the ideological underpinnings for the development of Tom’s of Maine’s purpose, mission and belief statements. Once this moral foundation was in place, Chappell’s next challenge was to manage the company in accordance with its stated values. Two situations are illustrative of the trade-offs presented by the new decision criteria. The first centered around the company’s application, in the early 1990s, to the American Dental Association (ADA) to receive its Seal of Approval for three fluoride toothpaste flavors. The ADA required a standard efficacy protocol that is lethal to rats. Rather than compromise its values, the company worked with the ADA to develop an acceptable test that could be conducted on human subjects and in 1995 received the association’s coveted seal. Because of the cumbersome process of developing the new protocol, the firm’s application for acceptance took several years longer and cost approximately ten times as much as it would have otherwise. Interestingly, a year later the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) suggested a new set of rules for fluoride toothpaste that only involved testing on animals. Tom’s strenuously lobbied the FDA to modify these rules and eventually identified a non-animal protocol that was acceptable to the agency.

The second situation occurred during the formulation of plans for the new wellness line. It was determined that the company could save $250,000 if it located the entire production and packaging operation for the product line in Vermont as opposed to the original thought of extracting herbs in Vermont and shipping them back to Maine for packaging. Rather than make the financially rational decision, Chappell, adhering to the company’s commitment to the Kennebunk community, split the work between the two locales.

In 1999, Tom Chappell summed up his philosophy of business decision-making in his second book, Managing Upside Down: The Seven Intentions of Values-Centered Leadership. (Chappell, 1999). Here he rejects the concept of managing for maximum financial gain and instead argues for reversing the values of American business by placing social and ethical responsibilities at the apex of the business goal hierarchy. He further asserts that if a company makes people and other entities the central focus of its decision-making, it will be rewarded through the marketplace with growth and profits. He underscores this assertion in the book’s introduction, “I have been running our company according to a mission of respecting customers, employees, community and the environment and we are creating more products and making more money than I ever dreamed.”

The books title, Managing Upside Down, also refers to flattening the organizational hierarchy and empowering people and teams at the lower end of the structure. Indeed, Chappell credited the gargantuan expansion of the company’s product line during the last three years of the 1990s to the creativity and follow-through of his newly empowered product development teams (known in the company as Acorns).

Chappell devotes a major portion of the book to what he calls the seven intentions of values-centered leadership – Connect, Know Thyself/Be Thyself, Envision Your Destiny, Seek Advice, Venture Out, Assess, Pass It On. The intentions are guidelines for managers who desire to run profitable businesses that are also socially and morally responsible. After publication of the book, Chappell established a nonprofit educational foundation, The Salt Water Institute, located in Boulder, Colorado, to teach these “intentions” and his overall philosophy of managing through moral values. (May,2000).

GIVING PROGRAMS

Tom Chappell perceives his company as a social and moral entity as well as a business organization and has fashioned a body of policies and programs to help realize this goal. These initiatives include policies in the areas of environment, animal rights, consumer issues and community and environmentally-based giving programs

Tom’s of Maine has committed to donating 10 percent of its pre-tax profits to non-profit organizations. In the early years when profits were lean, the company confined most of its giving to community organizations and environmental groups in Maine and Massachusetts. As profits grew and more money became available, donations to charities widened in scope and dollar amount.

The company’s grant program was divided into the four general areas of education, the arts, the environment and indigenous peoples. Approximately 40-50 grants per year were awarded either in the form of one-time grants or multi-year pledges. Most were in the $500- $5,000 range with larger amounts reserved for the multi-year pledges. Beneficiaries included Harvard Divinity School’s Center for the Study of Values in Public Affairs, the Maine Audubon Society, and elementary education programs in Maine for teaching about the environment.

An early grant from the company began the curbside recycling program in Kennebunk. The program was eventually funded entirely by the local community. Other

Donations went to the Rainforest Alliance, Maine Women’s Fund, Maine Business for Social Responsibility, the National Parks and Conservation Fund and a project in Portland, Oregon to protect its regional watersheds.

Tom’s donated some of its charitable dollars to mass communication. It sponsored the national environmental radio program E-Town. In 1999, Tom’s of Maine was the sole corporate sponsor of “Reason for Hope,” a PBS documentary abut the scientist/conservationist, Jane Goodall. The company viewed that sponsorship as a natural fit because it shared common values with Dr. Goodall. Prior to sponsoring the television special, the company for two years had been contributing to the Jane Goodall Institute and the related “Roots and Shoots,” an international environmental and humanitarian teaching program. In support of this program, the company included coupon inserts with its products that encouraged customer to mail back the coupons. In return, Tom’s promised to donate one dollar for each coupon returned. Additionally, the company offered to pay the $25 initiation fee for any school or community wishing to establish a Roots and Shoots program.

Finally, Tom’s of Maine made donations to various needy causes. For example, in April of 1999 it sent 50,000 bars of soap to the American Red Cross for needy families in Kosovo.

ENVIRONMENTAL POLICIES

In addition to its giving to environmental causes, Tom’s introduced pro-environmental practices in its operations. Toothpaste was packaged in aluminum tubes that could be recycled when empty, rather than the less expensive, non-recyclable plastic laminates used by most other manufacturers. Moreover, its toothpaste as well as some of its other products was packaged in 100 percent recycled paperboard cartons of which 65 percent was post-consumer content.

Mouthwash and glycerin soap was packed in natural color HDPE #2 plastic bottles which were considered better for recycling than other options. Shampoo was bottled in containers made from recycled milk jugs; and those bottles were, in turn, recyclable. All leaflets that were enclosed in the packaging were printed on dioxin-free paper using soy based inks. All outgoing products were shipped in boxes made from 95 percent post-consumer cardboard. All of Tom’s products were biodegradable.

In the mid-1990s the company installed a moss-filtration that allowed for 80 percent of the bio-burden to be removed from the factory’s waste water. With this system, by the time the water reached the leaking bed in a field near the manufacturing facility, it had run through a tank containing layers of peat moss, stone, gravel and sand removing the majority of its pollutants. (Wolfson, 1995). Additionally, the company’s farm in Vermont, where the botanical ingredients for its wellness line were grown, practiced sustainable harvesting of herbs and was certified organic.

Respect for animals was an important value at Tom’s. Consequently, the company did not use any animal ingredients in its products. Moreover, as noted earlier, the company did not use animal testing to establish the safety of its products, believing that such tests were neither the most effective nor the most humane way to ascertain product safety. In 1991, the company extended its prohibition on animal testing to its suppliers, requiring them to sign a written agreement that the ingredients supplied had not been tested on animals. (Company document).

CONSUMER POLICIES

Tom’s of Maine’s mission emphasized full disclosure of product information and open dialogue with its customers. From the beginning the Chappells listed all ingredients contained in their products on the packaging along with the sources of the ingredients and an explanation of their purpose. They believed that this policy built customer confidence and loyalty.

A related trust-building measure was the signature of Kate and Tom Chappell on all company products. Yet another trust-building policy of the company was to answer every letter from customers with a personalized return letter. Organizationally, this was the responsibility of the company’s Consumer Dialogue Team. This was no small task since the firm received some 10,000 letters per year (The team estimated that 80 percent of them represented positive customer feedback).

As another means of communicating with its customers, Tom’s included inserts with many of its products. On one occasion the company teamed up with Leave No Trace, Inc., an organization that promoted responsible outdoor skills. The inserts from that campaign stressed the six principles of Leave No Trace and provided additional environmentally responsible tips for campers.

Tom’s established a factory tour in 1993 as yet another avenue for connecting with its customers. The tour was typically led by one of the Chappell children. The company also developed a virtual tour on its web site for those who could not travel to Kennebunk.

ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN

Tom Chappell described the organization structure at Tom’s of Maine as a triangle inside a circle. The circle represented the team which was the basic unit of organization. Teams met in circles ( There were no elongated conference tables at Tom’s) to emphasize equality and encourage everyone to contribute ideas. Chappell credited the circle concept with the procreation of many of the innovative ideas and solutions that helped the company grow. He asserted, “The power of the circle is in its openness; it is the place where you are willing to open up and listen.” (Chappell, 1993, p. 119). He also credited the circle with improving employee morale.

The triangle, on the other hand, symbolized the company’s authority structure. As Chappell saw it, Tom’s was not a consensus organization. There was a leader on each team who was accountable to a higher manager and there was a clear chain of command. Ideally, the two systems – circle and triangle – worked in harmony. The circle encouraged participation and creativity. The triangle provided an apparatus for decision-making and accountability.

Tom Chappell also saw intentional diversity as a critical element of the company’s organizational design. After returning from Divinity School he came to the conclusion that diversity in hiring was not simply a moral responsibility but could also lead to marketplace advantage for the firm. He explained his thinking this way, “It was not long before I realized that the more sensitive my executives and I could become to the differences of the people we were trying to serve, the more perspectives we could plug into our discussions about product design, business strategy, and customer service and the more broadly the company could range to meet its financial objectives. We had to listen to as many different sources as possible, both inside and outside the company.” (Chappell, 1993, p.134).

Since Tom’s was essentially a male-dominated company through most of its history, Chappell made bringing more women into the company a priority. By 1993, 40 percent of the workforce was female and two key department managers were women.

Tom saw diversity as much more than simply hiring and promoting women and people of color. He saw it as a much broader concept encompassing factors such as age, education, experience and background, believing that a diversity of perspectives combined with an openness of a circle results in more innovative and effective business decisions. In support of its diversity goal the company had a policy of open hiring for all jobs. In other words, when a job became open, all candidates, inside and outside, were given equal consideration. The thinking was that only hiring from within the company leads to greater homogeneity, the very opposite of what the company hopes to achieve.

CULTURE AND HUMAN RESOURCE POLICIES

Chappell, after returning to the company full-time, devoted much of his time to formulating the company’s mission and beliefs, and to trying to mold a corporate culture that personifies these tenets. Commenting on one of the bigger mistakes he made, Chappell noted that simply handing down the company’s mission and beliefs is not enough, that it is important for the staff to see the company mission in action and that “you have to do the training.” (Adams, 1999). In practice this includes setting the example through his own behavior and decisions, encouraging and rewarding the people who “live the mission”, and holding workshops and seminars on topics of company values and behavior.

Tom’s policy on volunteerism is one prominent way the company tried to live its mission. Under this policy, employees were encouraged to spend 5 percent of their paid work time ( two hours per week or 2.5 weeks per year) doing volunteer work for nonprofit organizations of their choosing. This policy was instituted in 1989 and proved popular with employees as well as helpful to beneficiaries. Volunteer chores were as varied as the interests of Tom’s diverse workforce. In one unique example, an employee brought her dog once a week to a nursing home to provide comfort and companionship for the residents.

In addition to volunteerism, the company occasionally organized day-long projects that might include as much as one-third of its workforce. In once instance, fourteen employees, including Tom Chappell, drove to Rhode Island and spent the day helping clean up an oil spill. One of the participating employees commented afterward that the venture was not only helpful to the people of Rhode Island but also was a bonding and team-building experience for the participating employees. (McCune, 1997).

The company provided generous benefit packages to its employees including four weeks of parental leave for both mothers and fathers (adoption and foster care were included), as well as offering flexible work schedules, job sharing, and work-at-home programs. Childcare and eldercare referral service was provided and childcare was partially reimbursed for employees earning less than $32,500 annually. Largely as a result of these family-friendly policies, Tom’s was named as one of the 100 best companies for working mothers for six straight years between 1994 and 1998.

Other employee-friendly practices were simple but effective. Examples include bringing in a masseuse for the employees once a month and providing fresh fruit at both the corporate headquarters and the factory. The sum total of the variety of such practices was very low turnover. (Adams, 1999).

CONCLUSION

Tom Chappell’s accomplishments were recognized by the American National Business Hall of Fame in 2006 when he was named a hall of fame fellow. That designation certified him as a role model for students and business leaders according to the hall of fame’s board of electors (25 university business school professors drawn from across the United States). Tom’s selection is meant to send the message that business and social responsibility are not only compatible but also the source of deep personal satisfaction and a sense of fulfillment for those business leaders who follow Tom’s example.

REFERENCES

Adams, C, “Breakaway (a Special Report): The Entrepreneurial Life – Upfront: Brushing Up on Values,” The Wall Street Journal, September 27, 1999.

Chappell, Tom. The Soul of a Business: Managing for Profit and the Common Good. New York: Bantam Books, 1993.

Chappell, T, “Letters to the Editor”, Harvard Business Review, Sept./Oct., 1997.

Chappell, Tom. Managing Upside Down. New York: William Morrow and Co., 1999.

Forbes, Vol. 156, Issue 13, p. 16.

May, T., “You get what you give,” Natural Food Merchandiser’s New Product Review, Spring, 2000.

McCunre, J., “The Corporation in the Community,” HR Focus, March 1997.

McCune, J., “Making Lemonade: Companies must try (and sometimes fail) in order to succeed,” Management Review, June 1997.

Popovich, B., “Focus Report: Cosmetics/Personal Care 2000: Multi-Benefits Top Dental Care Market,” Chemical Market Reporter

“Tom Chappell, Minister of Commerce,” Business Ethics, January/February 1994

Tom’s of Maine, various in-house publications and postings on the company web site (www.tomsofmaine.com).

Wolfson, W., “Brushing up on business,” E. Magazine: The Environmental Magazine, July/August 1995.

ANBHF Laureates

Our laureates and fellows exemplify the American tradition of business leadership. The ANBHF has published the biographies of our laureates and fellows.

Some are currently available online and more are added each month.